Trump's Tariffs on Canada: The Real Issue

Canada's economy, especially its farm and food sector, bears little resemblance to America's. Their "supply management" scheme would be illegal, even unimaginable in the USA.

President Donald Trump uses emergency powers reserved for national security to impose 25 percent tariffs on aluminum, steel, and other products, although they alternate from being off or on. Those powers ostensibly are for reducing a dramatic growth in illicit fentanyl exports from both Canada and Mexico, but in reality, it’s a trade war, not a drug war.

The stakes are high regarding the US-Canada trade relationship, which is the world’s largest, at just under $1 trillion annually.

And while America has its addiction issues to the illegal opioid, Canada has an addiction problem of its own: its highly protectionist “supply management” system. And Canada is very reluctant to give it up.

Understanding their supply management problem means understanding the heart of the US government’s frustration regarding trade with Canada. Canada's supply management system is nuanced and complicated, which is probably why no one in the media—nor the Trump Administration—has attempted to explain it. This system conflicts largely with the export-driven US farm sector.

So, here goes, with apologies for oversimplifying a complicated issue. Still, Canada’s refusal to address long-festering trade issues—even involving inter-provincial trade in the 51st state of our northern neighbor—is at the heart of our longstanding brouhaha with them. Once you get this, you’ll understand what essentially prevents converting North America into an economic powerhouse (the USA is not blameless) and the vast opportunity Trump is forcing our neighbors - and us - to consider.

The reality is that Canada is so addicted to their highly protective economic system that even the most conservative politicians in the nation won’t deal with it. Conservative Opposition Leader Pierre Poilievre (POLLY-ev) explains via Canada’s Western Standard:

Federal Conservative leadership candidate Pierre Poilievre says he has no plans to change Canada’s Soviet-style supply management of certain sections of Canada’s agriculture sector.

The Calgary-born MP spoke with the Western Standard’s Cory Morgan on his daily show Triggered.

Poilievre said he isn’t proposing to change current agriculture price and production controls which create artificially high prices by setting production quotas and large import taxes and prohibitions on imported dairy and other products.

“…The reason is that the farmers who own the quota have had to pay millions of dollars for it,” said Poilievre.

Farmers must hold a permit, referred to as “quota” to sell their products to a processing plant, which is often more expensive than the farms themselves.

“And furthermore, if we brought them [supply management controls] out, then it would cost more to do that than it would to keep the system that is in place right now,” he said.

Oh, sure, Canada has moved incrementally towards a more free market posture, at least with a couple of commodities. Under former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Canada partially deregulated its supply management system in 2012. It phased out its national wheat board, which issued permits with quotas to wheat farmers and negotiated prices on their behalf. Canada also limited wheat imports with punitive tariffs. Canada controlled the prices of goods by restricting production and competition from abroad.

What was the result of Harper’s elimination of the Canadian Wheat Board? Let’s ask Canada’s Western Producer:

There has been much change in the western Canadian grain industry post-2012. New grain companies have arrived from overseas and south of the border; new terminals have been built in Vancouver; loop-track systems are allowing shuttle trains to chop days off traditional turnaround times and the railways have poured money into expanded capacity.

“There has been a great deal of investment, on all levels, in the transportation and handling system,” observed Barry Prentice, a long-time University of Manitoba transportation systems expert and analyst of the complexities of the western Canadian grain handling system.

“Much of that probably wouldn’t have occurred if the monopolies had stayed in place.”

Grain companies jumped on the chance to control grain from the point of purchase (the farmer) to the end-use customer. Railways were happy to see an end to the CWB’s ability to influence how they ran their systems.

Not everyone agrees. Terry Boehm, the former chair of Canada’s progressive National Farmers Union, cites the destruction of “economic justice” and other lefty buzz words.

If adopted in the United States, Canada’s cartel-run supply management system would violate almost every anti-trust law in our books. Let me explain how it works via a real-life example, at least in the food sector. I spent most of two decades directing Campbell Soup Company’s (now called Campbell’s Company) global government relations activities. Campbell used to own and operate significant food processing facilities in Listowel and Toronto (both were closed by 2018) and dealt with Ontario’s provincial “marketing boards” to procure vegetables and other ingredients.

Here’s a slight oversimplification of how it works.

Say you own a canned foods plant in Ontario and must procure vegetables, from asparagus to carrots. You can’t directly contact the farmers you trust to provide the highest quality carrots for processing or even dictate how you deliver them (e.g., carrots from preferred “belt bottom” trucks versus dump trucks - trust me, it matters).

You’ll need to contact the appropriate marketing board of Ontario Processing Vegetable Growers. They will “negotiate” your price, select your suppliers, and decide how the products are delivered to your factory. You have little say on which farmer or farmers you prefer. The cartel members will determine that, thank you very much.

Ontario’s “conservative” (tiny “c”) government, led by populist-nationalist Doug Ford, who was just overwhelmingly reelected (February 27th), began in 2019 to depower the tomato and carrot cartels' marketing boards, over the objection of the OPVG.

Note to my Republican friends: Don’t compare the GOP to the Conservative Party of Canada. It’s the left of most Republicans. Canada is not a politically conservative country, as we define it. When Poilievre says he wants to make Canada the “freeist nation on earth,” it likely means as “free as possible” in a center-left nation and still less free than the United States. Canada is more anti-gun ownership, more pro-abortion, more pro-socialized medicine, and way more pro-euthanasia than the United States.

What happens if a drought or disease curbs vegetable supply from Canadian farmers? You can reach out to vegetable growers in Michigan or Ohio only after it’s certified that the supply isn’t available in their country. If you’re an American farmer who wants to sell your vegetables to a Canadian processor, good luck forget about it.

My Canadian friends will tell you that American trade isn’t any more “free” than Canada’s. With rare exception, that’s mostly not true. Canadian hothouse tomatoes and foreign-grown fruit and vegetables can be found in almost any American grocery store. In the US, there are very few quotas or limits on imported commodities and products (sugar is a significant exception, mainly because Canada produces very little but allows unfettered access to cheaper world prices. As a result, a lot of US candy is manufactured in Canada). Under international trading rules, Canadian chicken growers and processors must allow some imports, but they’re restricted to a percentage of sales. They only enable more imports as domestic production and sales grow enough to comply with international trade agreements.

The American farmers’ focus on exports and export markets is very different from Canada’s focus on its domestic market and protecting it for domestic growers. And therein lies the heart of the friction. The Trump Administration, which enjoyed strong support from rural America and its farming communities in the 2024 election, is about growing export markets for them. The tariffs are a tactic, a negotiating ploy to get there—short-term pain and uncertainty for long-term gain. We’ll see how long impatient Americans will put up with it.

Many other significant differences exist in how Canada and the US regulate food and commerce. It was a big deal nearly a decade ago when the US and Canada agreed that their food safety systems were comparable enough that they recognized and accepted each other’s food safety inspections. It took decades for the US and Canada to agree to that.

The longest-running dispute between the US and Canada likely involves softwood lumber, with beef a close second. Canadian lumber producers are subsidized by their federal and provincial governments mainly because they harvest from “crown” lands (owned by the government) at no or little additional cost. After years of disputes and expired agreements, Canadian lumber producers had unfettered access to US markets. Still, the Biden Administration hiked tariffs on specific companies from about 9 to 14 percent last year.

Poilievre may want to protect Canada’s supply management system. Still, his approach to energy—building pipelines and LNG (liquified national gas) terminals and finding new customers for its ample petroleum reserves—could work for food and other commodities if they were interested. Canada, in particular, has a massive housing crisis, partly attributable to an influx of immigrants over the past ten years and stiff regulations on new home construction.

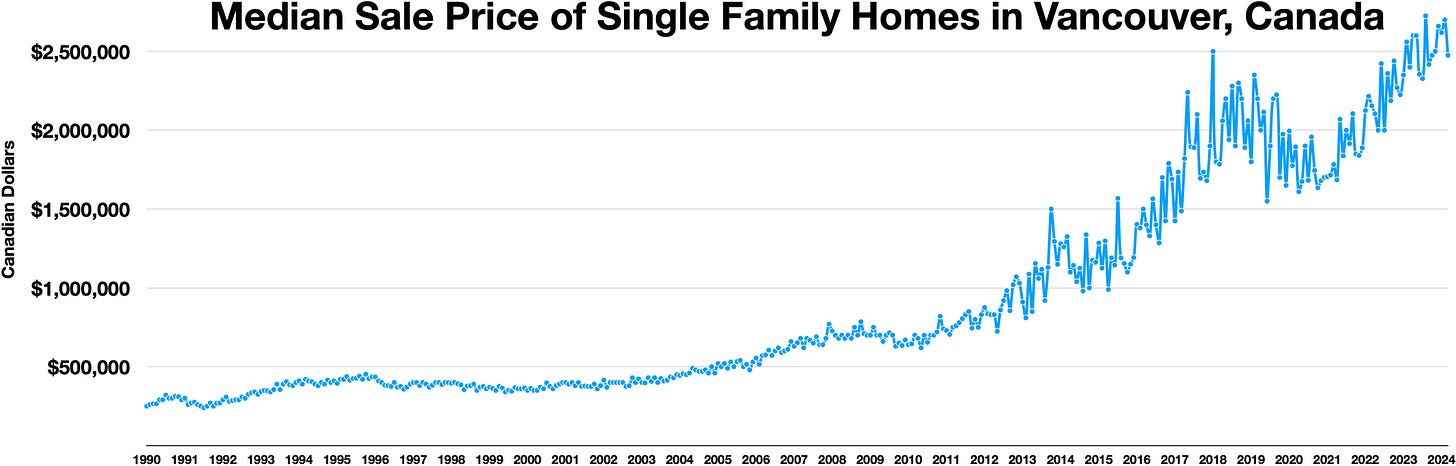

While the US housing “bubble” popped with the 2008 financial crisis, Canada’s didn’t. Homes in populated cities such as Toronto routinely sell for north of $1 million, and Vancouver is among the most expensive cities on Earth in which to rent or buy a house and live.

The recent surge in Canadian nationalist sentiment, due almost entirely to Trump’s bombastic rhetoric about making Canada the 51st state, referring to outgoing Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as “Governor,” and his punitive tariffs is understandable. Still, it ignores the realities of a highly regulated and protected economy. They seem afraid of competition. Given the US economy and population’s massive size difference over Canada, and the USA’s overpowering cultural influence over them (nearly 90 percent of Canadians live within 150 miles of the US border), that’s also understandable. Half Canada’s population lives below the 49th parallel, often associated with their southern border.

Canadian politicians are imposing counter-tariffs on US products, but access to the US economy is far more vital to them than our access to theirs. And they know it—so does the Trump Administration.

Almost 70 percent of Canadian exports go to the United States, and about 20 percent of US exports go to Canada. Those are significant numbers for both countries, but you get the point. Exports count for a third of Canada’s GDP.

I doubt Trump is personally familiar with the intricacies of Canada’s supply management system. Still, he has undoubtedly heard about it from his advisors, especially from American farmers, producers, and processors who deal with it. Until Canada changes its tune and frees its industries by moving from supply management to supply-side economics, its economy will continue to trail ours in meaningful ways, from investment and innovation to income. Part of the problem is that the government in Canada consumes an estimated 64 percent of the Gross Domestic Product if tax expenditures and price regulation are included.

While the US has economic challenges, according to Canada’s Fraser Institute, median wages and salaries are lower in every Canadian province than in every US state. Booing the US national anthem won’t resolve their housing, health care, and growing economic woes. Perhaps they should look in the mirror.

Great explanation!

Loved the photo of you with the Canadian PM. Great information.