The Real Issue: Non-Tariff Barriers

While everyone is focused on Trump's Tariffs, the more significant issue for many US exporters and importers is non-tariff trade barriers. There are lots of them, and they'll never go away.

The two most complex and nuanced issues I confronted during my more than two decades as a food lobbyist were 1) the US dairy program and 2) international trade. I shudder even now to think of them.

I studiously avoided the former and jumped into the latter with great trepidation. There is an entire underworld regime of government agencies, led by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, which is part of the Executive Office of the White House. Scores of other agencies and subagencies are also present throughout various departments, including the U.S. Departments of Agriculture (US Foreign Agricultural Service) and Commerce (US International Trade Administration).

I also didn’t like trade issues because progress was incremental, at best, and often elusive. Little changed no matter how much dust the Clinton, Bush, Obama, or even the first Trump Administrations stirred.

Additionally, there is an equally complex and massive infrastructure of consultants, trade associations, media publications, and government affairs professionals specializing in international trade. Even as the director of global government affairs for a Fortune 250 manufacturer with operations worldwide at the time, I rarely hired consultants; however, I did employ a terrific firm a short walk from the USTR’s offices, across from the Eisenhower Executive Office Building on 17th Street, NW, in downtown Washington. I needed help navigating international trade rules, regulations, and negotiations, and they expertly and patiently provided the assistance I needed.

Additionally, advisory committees are established by Congress via the Federal Advisory Committee Act. I served on one, a technical advisory committee on trade in processed foods (there are many others), co-managed by the US Trade Representative and the US Department of Agriculture and requiring a secret clearance so we could learn and discuss (among ourselves) details of confidential negotiations on things like so-called free trade agreements, including dispute resolutions, and provide our advice and counsel for government negotiators.

Advisory committees serve a valuable purpose for both domestic industries and the government. Rest assured that, to the best of my knowledge, the participating company representatives did not try to exploit them for propriety gain, nor would government officials tolerate it. This was a level playing field, and I trust that it still is.

Our discussions focused mainly on non-tariff barriers for exports, importing ingredients and parts used in our products and production facilities, and pending free trade negotiations (may they rest in peace). Nearly all foreign governments, particularly those of the European Union, utilized these barriers to restrict or exclude specific U.S. commodities and products, but they were hardly alone.

For example, finding an American-grown steak anywhere in Europe can be challenging. Despite a World Trade Organization (WTO) resolution in the USA’s favor, Europeans refused to admit much US beef due to concerns about using growth hormones in cattle raising (the hormones don't show up in your steak, so chill out). In 2019, the Trump Administration negotiated a tripling of US beef access to the European market, utilizing Section 301 of the Federal Trade Act of 1974. That’s a frequently used provision dealing with “unfair trade.” However, an enforceable dispute resolution mechanism by the WTO, which was established in 1994, has eliminated a lot of Section 301 disputes.

I see your eyes glazing over. Pay attention; your sandwiches are involved. There may be a test.

The problem with the WTO is that its dispute resolution process is lengthy and cumbersome, often taking years to complete. But offenders don't care since “enforcement” won’t happen for the foreseeable future, and they can take their time to comply.

So-called “free trade agreements,” such as the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (set to be renegotiated next year), aren't truly “free.” Canada protects its highly socialized “supply management” regime, while the US restricts the imports of Mexican and foreign sugar. Some US tomato growers, especially those producing fresh tomatoes, complain about the influx of lower-priced Mexican fresh tomatoes. There are almost no country of origin requirements for food service, including where the tomatoes for your Chipotle, McDonald’s, or Panera sandwiches come from, compared to packaged foods.

And things that the US promoted decades ago, such as maquiladoras on the Mexican side of the US border - manufacturing facilities designed to improve economic conditions and reduce illegal immigration while allowing US companies to employ cheaper labor and ship products nearly duty-free - are now disfavored. There are about 3,200 maquiladoras along the Mexico-US border. What are they supposed to do now with their massive capital investments?

So what forms do non-tariff barriers take? Licenses and certificates are two examples. Food safety and related standards, including “standards of identity” - such as what qualifies as a “jelly bean” or “chocolate,” for example - are another tool. What often qualifies as chocolate in Australia (think of their iconic Tim Tam cookies, once owned by Campbell’s Company but no longer) doesn’t meet the definition in the USA. Canadian confectioner David Ganong chose to forgo selling his jelly beans in the US more than a decade ago since they didn’t meet the American standard of identity. Perhaps that’s changed over the past decade.

Iconic Kraft Macaroni and Cheese boxes made in Montreal for the US market aren’t called Macaroni and Cheese in Canada. Maybe it’s a marketing difference, but there are differences in the ingredients (the Canadian version lacks cheddar cheese and butter). I’ll have to ask my Heinz-Kraft friends why that is the case. The US standard of identity for macaroni and cheese requires cheese and butter. Maybe Canada doesn’t. Canadians also have a penchant for PepsiCo-owned Lay’s Ketchup and Chicken-flavored potato chips and Campbell’s Company Salt and Vinegar Pepperidge Farm Goldfish crackers, which are very hard to find in the US—nothing to do with trade, just local preferences.

I recall being told that the FDA didn’t like my former employer marketing Salt and Vinegar Goldfish due to its high sodium levels and that Goldfish is primarily considered a children’s product. I know they’ve never tried to ban the product, which I love. You’ll occasionally find Salt and Vinegar Goldfish in Canadian sports bars. They go well with ice hockey and beer; given the approaching Stanley Cup playoffs, I will find them.

Labeling requirements, such as those specifying the country of origin, are popular with consumers and imposed by governments, including the US, to help promote domestic sources. Don’t think for a second that this is going to change. The WTO says that’s fine, so long as such labeling requirements aren’t used to disparage the country or product of import.

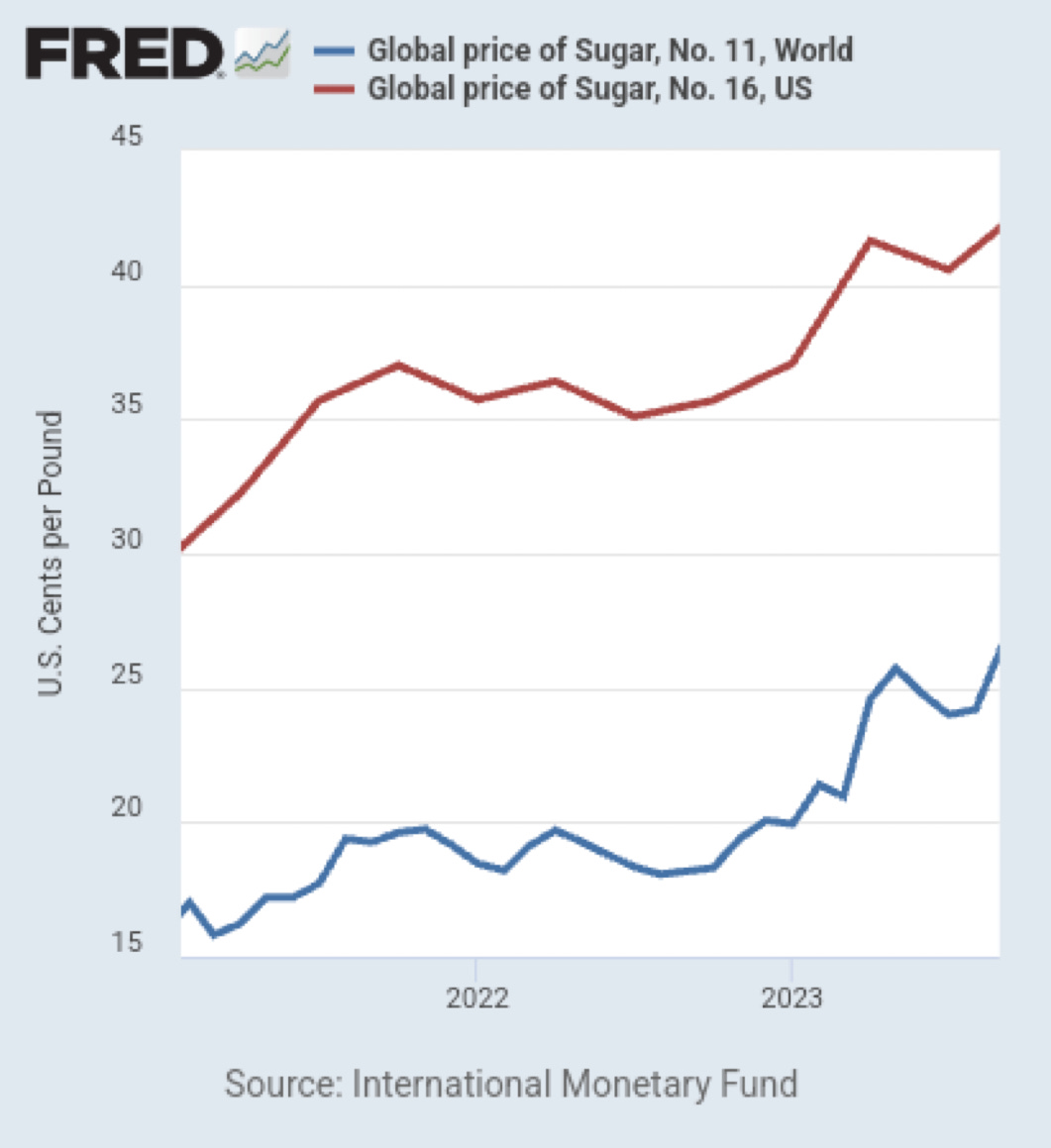

Additionally, as I've explained, some countries, such as Canada, limit what can be procured from outside their borders. It’s part of their Soviet-style “supply management” program. The US employs quotas to restrict sugar imports, protecting domestic suppliers, including sugarcane growers in Florida and sugar beet farmers in Minnesota and other upper Midwest states. As a result, US candy makers have shifted production and jobs to Canada to access lower sugar prices, and no amount of tariffs will bring them back until the US sugar program terminates. And that ain’t happening.

Maybe your head is spinning like mine used to over this Byzantine world of international trade. No one, especially the United States, can avoid being blamed for various politically inspired protectionism and trade restrictions.

That’s why I was hoping that Trump could pause new tariffs—90 days or so, renewable depending on the pace of progress towards eliminating tariff and non-tariff barriers—while all this gets negotiated. My financial portfolio would appreciate it. Given the enormous complexity of the details and the number of trading partners and stakeholders, it will take time. For every country involved, there will be non-negotiables where domestic politics rule—more than you know.

I recall touring a former employer's manufacturing plants in Toronto years ago (now shuttered) and being struck by the twin stacks of separate pallets used to transport finished products into the US or Canada. That wasn’t a government requirement; the Canadian and US retail industry’s requirements differed. Governments don’t always impose non-tariff trade barriers. They’re often either demanded by domestic industries or imposed by them.

Among my least favorite US non-tariff barriers are “Buy America” laws and the “Jones Act,” which triggers many protectionist friends. I’ve told the story of how my former employer, a US-based manufacturer, was prohibited from selling its Canadian-made soup, which is comprised chiefly of US ingredients, to the US military, thanks to the “Berry Amendment.” We lost out to a US plant owned by a Netherlands-based company. Never mind that sensitive electronic military equipment from Canada was okay, but not soup. Go figure.

The Jones Act is a century-old law designed to protect and grow our nation’s merchant marine fleet, which it hasn’t. It requires cargo ships operating between two U.S. ports to be American-made, American-crewed, and American-registered. Some US ports, such as the US Virgin Islands, have won partial exemptions; Puerto Rico, not so much. Due to higher shipping costs, Puerto Ricans pay more for products when they can get them. Sometimes, shipping products from other countries on ships flagged, made, or crewed by non-US sources is cheaper and more plentiful.

I tried to lobby for partial exemptions from the Jones Act for Puerto Rico years ago but was met with a reception akin to dengue fever on Capitol Hill.

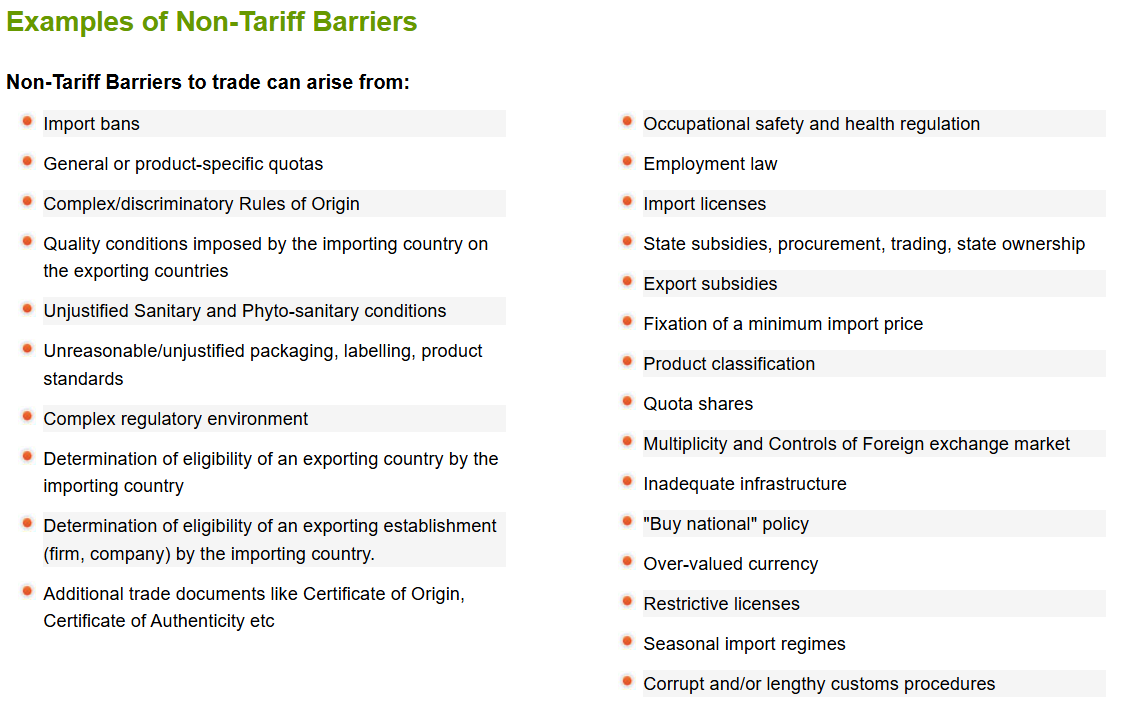

Here is a reasonably comprehensive list of other non-tariff barriers.

Wouldn’t it be funny if Donald Trump, the nationalist and protectionist, reordered a genuinely more open and free global trading system through his gambit over tariffs? In the words of the late John F. Kennedy, more open and competitive markets would serve as a rising tide that would lift all boats.

Of course, that’s not going to happen since every country wants to protect and promote its industrial bases for national security reasons and primarily for domestic politics. However, moving toward more open international trade would benefit everyone, spur innovation, and lower prices through increased competition.

The bottom line: The more things change, the more they remain the same. Call me a cynic, but I do not anticipate many changes when the Trump-stirred dust eventually settles, no matter how much he kicks up.

Always well-researched and informative.