What to Make of the Latest Mar-a-Lago Machinations?

It's hard to ascertain from media reports - many from bizarre DOJ and FBI leaks - to figure out what's happening with the dubious Mar-a-Lago raid. Professor Jonathan Turley to the rescue

It’s been hard both to grasp and keep up with the machinations of the FBI raid (spare me the assertions that the FBI doesn’t “raid”) of Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence in Florida a month ago while he was away.

Legal experts from National Review’s level-headed former federal prosecutor Andrew C. McCarthy have been educational, fair, and insightful. Others, not so much. These so-called legal experts’ often bizarre and partisan ruminations about the raid or the appointment of a “Special Master” soil what’s left of their increasingly comical reputations.

Reminiscent of the Russia collusion hoax reporting, clowns in the mainstream media continue to pass along anonymous leaks from malevolent government sources without question or honest verification. There’s no better than the Washington Post’s claim that the raid involved information about “nuclear” codes and the like. Fortunately, that story didn’t have legs other than to walk the Post’s reputation back into the trash bin.

Yet, there’s still much we don’t know about the reason behind (the January 6th Capitol violence? The Russia-Collusion hoax?) the raid involving an estimated 30 agents.

This much is obvious. The President has the ultimate authority to declassify documents. Presidents take classified documents with them when they leave office. Trump’s office had been negotiating with the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) over “classified” documents in the former President’s possession. Subpoena power to secure the documents was also bypassed for the unprecedented raid.

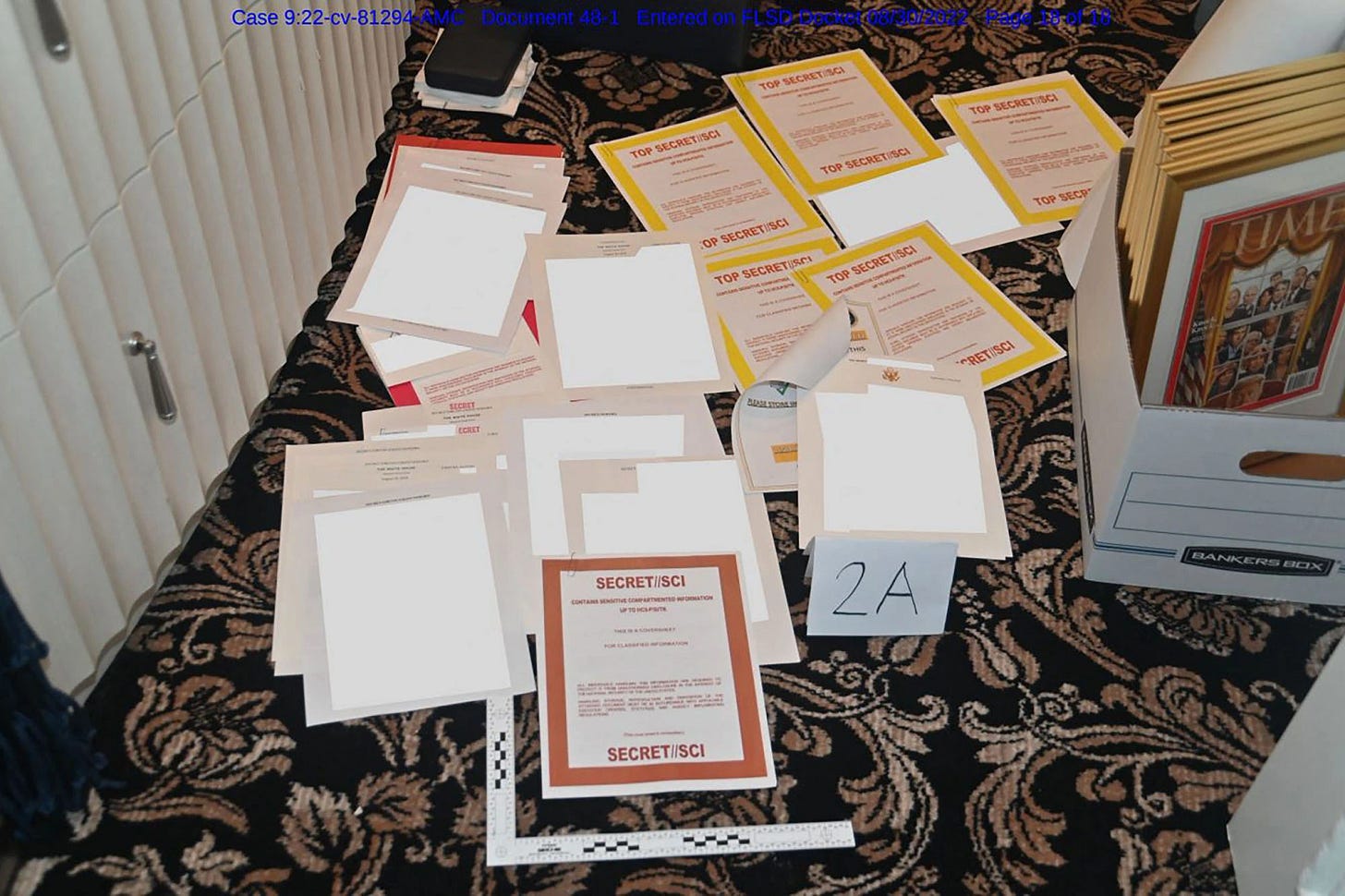

The warrant and affidavit for the raid were unusually broad and included searching Melania’s wardrobe and now, we learn, his son Barron’s room. The magistrate who signed off the warrant has an odd past that has inspired all kinds of conspiracies. The FBI released weird photos of empty file folders.

Some of the most interesting commentaries come from Kash Patel, who assisted the outgoing President with moving documents to Mar-a-Lago. Patel also seems to be in the sites of a politicized FBI and Department of Justice leadership, although not the subject of any investigation, as far as we know. Patel claims the same people involved in the Russia hoax investigation are behind the Mar-a-Lago raid.

The appointment of a “Special Master” by a Federal District Judge (nominated by Trump, referenced by partisans to discredit her) raises new controversies. Fortunately, Jonathan Turley, a George Washington University professor and frequent blogger and commentator, comes to the rescue. No Trump fan, he has navigated these controversies as fairly as anyone. His latest today is worth your time.

In another defeat for the Justice Department, a federal court has ordered not just the appointment of a Special Master but halted the use of the seized Mar-a-Lago documents by prosecutors until the legal status of these documents is established (The ongoing intelligence security review of classified material can continue). As with the compelled release of a redacted affidavit, the Justice Department seriously overplayed its hand (as it did in earlier filings) in claiming that an appointment would undermine national security and making extreme, unestablished legal arguments. The ruling by U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon will not necessarily change the ultimate trajectory of the case but it will force critical reviews and rulings on issues from attorney-client privilege to executive privilege.

For weeks, I have been writing about both the value of an appointment of a Special Master to reassure many in the public of an independent review and to address unresolved and difficult questions over these documents. While brushed aside by many legal experts, the prosecution of Donald Trump would require courts to address some long-unresolved questions.

The appointment and review will cause delay but it was unlikely that the prosecutors would bring charges until after the midterm election anyway due to the long-standing policy.

The order also does not halt the criminal investigation, only the use of the documents. Prosecutors can still interview witnesses on what was known to be the content of boxes, what steps were taken to allegedly move or conceal material, and other issues critical to establishing crimes of obstruction.

Many faculty on the left continue the curious objections to a court seeking review of the FBI or not accepting its overbroad claims of authority. It is a bizarre shift that we have seen in other Trump investigations where liberals suddenly express shock that a court would countermand sweeping national security claims or seek to review the Justice Department’s review of material for privilege. It does not matter that there appears to have been mistakes by the taint team and that privileged material (as well as an assortment of private material from medical records to tax records) were seized.

The same breathless coverage followed the order that we have seen in prior Trump-related matters. AEI’s Neil Ornstein suggested that Judge Cannon is now engaged in obstruction by simply ordering a third-party review. The over-wrought response to this order is par for the course over the last six years.

Stephen I. Vladeck, a law professor at University of Texas and CNN contributor, expressed outrage at “an unprecedented intervention by a federal district judge into the middle of an ongoing federal criminal and national security investigation.” (Vladeck was one of the experts who previously supported an array of criminal allegations against Trump and pushed a false claim related to the clearing of Lafayette Park). While it is admittedly less common to use a special master in a criminal case, it is not “unprecedented” for a court to conduct in camera reviews of seized material. In this case, the court wants to use a special master to perform that function. Moreover, special masters are commonly appointed in the federal courts in an array of cases where judges need assistance in creating a record for a ruling on motions.

Keep in mind that The Justice Department itself recognizes that it may have gathered some attorney-client privileged documents in this ridiculously broad search. It allowed the seizure of any box containing any document with any classification of any kind — and all boxes stored with that box. It also allowed the seizure of any writing from Trump’s presidency. Judge Cannon notes that the Justice Department’s own taint team missed privileged material and rejects the government’s assurance that it still caught the errors (emphasis added below):

“Counsel from the Privilege Review Team characterized them as examples of the filter process working. The Court is not so sure. These instances certainly are demonstrative of integrity on the part of the Investigative Team members who returned the potentially privileged material. But they also indicate that, on more than one occasion, the Privilege Review Team’s initial screening failed to identify potentially privileged material. The Government’s other explanation—that these instances were the result of adopting an overinclusive view of potentially privileged material out of an abundance of caution—does not satisfy the Court either. Even accepting the Government’s untested premise, the use of a broad standard for potentially privileged material does not explain how qualifying material ended up in the hands of the Investigative Team. Perhaps most concerning, the Filter Review Team’s Report does not indicate that any steps were taken after these instances of exposure to wall off the two tainted members of the Investigation Team [see ECF No. 40]. In sum, without drawing inferences, there is a basis on this record to question how materials passed through the screening process, further underscoring the importance of procedural safeguards and an additional layer of review.“

Notably, Judge Cannon also rejected the blanket denial of possible executive privilege arguments by the Justice Department and correctly notes that the assertion of some privilege by a former president remains unresolved in controlling precedent.

The Justice Department may appeal the decision. Special masters are routinely appointed as an extension of the authority of the court to help create a record upon which the judge can rule. It is not common to see this type of review at this stage but this is hardly your common criminal case given the intersecting constitutional and attorney-client privilege claims. Such appointments are generally left to the discretion of the trial court by appellate courts.

Yet, that does not mean that appellate judges might not tailor the order (or even block it). For example, appellate judges could question the scope of the bar on the use of the documents. They could loosen the ruling to allow the use of some documents with classification markings or require threshold determinations to free up such material.

However, the appointment of a special master in my view was the right thing to do. It was unfortunately another step that Attorney General Merrick Garland could have taken but refused to do so. Garland has had at least four opportunities to take modest steps to assure the public on the department’s motives and means in this controversy.

You can read Cannon’s full order here.