US Senator Fred Harris (D-OK), RIP

The late Fred Harris, 94, passed away this weekend. An original prairie populist, he saw the mantel of populism shift to Donald Trump and Republicans. Did he set the stage for it?

“Populism” often defies definition or a shelf life. The US “House Populist Caucus" was created in 1983, consisting primarily of a handful of rural Democrats, and died shortly after that.

Background: Caucuses (Cauci?), officially called Congressional Member Organizations (CMOs), are a dime a dozen in the House and have semi-official status. Any funding they get comes from Members of Congress pooling their money to subsidize staff or permissible activities. Many aren’t funded at all. Any House Member can start one (the Senate doesn’t engage in that practice), and lobbyists often help organize and staff them to protect and promote the interests of their particular industry or cause. There are also Congress Staff Organizations (CSOs), but not as many.

When asked to define populism, the late Mike Synar (D-OK), a founding member of the House Populist Caucus, told Congressional Quarterly in 1983, “I call ‘em as I see ‘em.” Synar lost reelection the same way he won in 1978, in a Democratic primary (1994). He tragically died of brain cancer two years later.

A better definition of populism is championing the interests of “common people” over those of a powerful or ruling elite, perceived or actual. Is Donald Trump a populist? You bet. So were Communists Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, and Hugo Chavez until they became the elite. The famous George Orwell novel Animal Farm is about how that happens, at least on The Left™.

Populism is not defined nor limited by political ideology. It’s a political stratagem fueled mainly by resentment and a desire to upend the existing “order.” Wokeism and its cousin, progressivism, are forms of populism, as they incite resentment primarily based on race and perceived “oppression.”

Fred Harris, the former US Senator from Oklahoma, two-time Democratic presidential candidate, and longtime college professor, famously branded and symbolized populism during his political career, including writing a book entitled “The New Populism.” He passed away this weekend at age 94. The New Populism was one of twenty books he authored, most after he left politics in 1976.

Here’s how Harris defined populism in 2016 following Donald Trump’s first win, via Politico:

What exactly is “New Populism”?

“Well, it means whatever I say it means, because I dreamed it up,” Harris laughs, before explaining in his spry, Slim Pickens-like Oklahoma drawl: “Actually, what it means is that a fair distribution of wealth, income and power should be the specific goal of the country.”

While cynical, he’s not wrong, and I see many 2024 Trump supporters—MAGA voters—nodding vigorously. However, Harris sees the government as a legitimate redistributor of that wealth and power. How has that worked out? The government likes to keep and wield power, not distribute it. Many Americans believe the federal administrative state works not for them but for themselves.

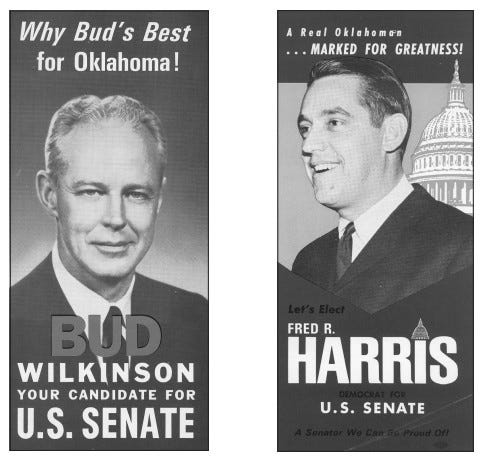

The jowly Harris didn’t start his career as a populist. Elected to the State Senate in 1956 - its youngest member at age 25 - he won a special election for a US Senate seat in 1964 following the death of Sen. Robert S. Kerr (D-OK). He not only upset appointed US Sen. J. Howard Edmondson - the former governor appointed himself to the Senate, and that rarely turns out well - Harris defeated legendary and famous Oklahoma University head football coach Bud Wilkinson in the general election. Lyndon Johnson’s coattails from his landslide win that year against Sen. Barry Goldwater (R-AZ) was enough to pull the 33-year-old Harris over the finish line. He was handily reelected two years later to a full six-year term.

He was quickly celebrated as a rising star in Washington, with strong ties to the oil industry, southern Democrats, and President Lyndon Johnson. So much so that he was called “Little Lyndon from Lawton.” But as his national ambitions grew, he moved left politically. Way left. But not before being seriously considered as Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s (D-MN) running mate in 1968, both for being geographically acceptable to southern Democrats but with a Civil Rights record that would appeal to northerners. Humphrey instead chose US Sen. Ed Muskie (D-ME). Following that tumultuous year, Harris briefly served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee in 1969.

“The issue is privilege,” Mr. Harris told The New York Times in 1975. “The fundamental problem is that too few people have all the money and power, and everybody else has too little of either. The widespread diffusion of economic and political power ought to be the express goal — the stated goal — of government.”

- New York Times obituary, November 24, 2024.

I encountered Harris twice during my career, first in Chickasha, Oklahoma, in 1975 during the early phase of his second presidential campaign. I was a college student and part-time reporter for the Chickasha Daily Express and was assigned to cover the one and only campaign event at a local restaurant in the community of 17,000. Harris faced stiff competition for Oklahoma delegates from US Sen. Lloyd Bentsen (D-TX) and Gov. Jimmy Carter (D-GA). Harris knew his campaign wouldn’t go far if he couldn’t win his home state.

Born and raised a Democrat in the one-party state (Democrats outnumbered Republicans 4:1 then) and the grandson of a beneficiary of Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” programs, I was attracted to Harris’s populism. I wound up the Grady County co-chair of his 1976 campaign. I spoke for him at the county Democratic caucus in 1976. I recall that we finished second to “uncommitted.” I remember that we defeated Bentsen, who soon withdrew from the race. The Carter folks successfully pushed for “uncommitted.” The state’s Democratic leadership, as I recall, was for the more electable Carter. Harris would go on to finish third in the Iowa Caucuses but dropped out shortly after a poor finish in New Hampshire’s Democratic primary. His brand of populism may have played fairly well in Iowa, but not in The Granite State.

As I look back, Harris’s positions on issues in 1976 were pretty far out, to borrow a phrase from that era. He proposed the abolishment of the CIA and ending support for foreign dictators. He called for creating a national energy company to “compete with the big boys,” which was pretty bold for a former Senator from an oil-producing state. He called for a guaranteed annual income and giving cash to the poor to buy food instead of vouchers (food stamps) so they could opt for restaurants instead of grocery stores if that were more convenient.

His first campaign for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination petered out when his campaign ran out of money in November 1971, having lost big donors over his radical move to the left on various issues, from the Vietnam War to domestic matters, including race relations and redistributing wealth and political power. At the time, it was the shortest presidential campaign in history.

Another Harris probably broke that record in 2020.

He served on the Kerner Commission following race riots in urban centers in 1966 and blamed white supremacy. In 1971, Harris opted to run for President instead of reelection to a second full term in the Senate the following year, choosing his presidential ambitions over his more conservative (if still Democratic) state. Harris moved away from his loyalty and ties to southern Democrats for northern liberals such as Sen. Walter Mondale (D-MN).

Good thing: his Democratic primary opponent, US Rep. Ed Edmondson (D-OK), was leading him 2:1 in polls before Harris opted for a White House run. When his campaign fizzled, he finished his Senate term and began plotting a second presidential campaign. Edmondson would lose that year to the late Dewey Bartlett (R-OK) as Richard Nixon won a national landslide.

After his 1976 campaign ended, he mostly gave up politics for the life of an author and college professor in New Mexico, serving a brief stint as chair of the New Mexico Democratic party.

My last communication with Sen. Harris came in late 1995 when he wrote me, the Secretary of the Senate, looking to replace a lost US Senate pin. I was happy to provide him with one at no charge and wrote to remind him of our previous connection, thanking him for helping launch my involvement in politics. I suspect he was surprised to learn that a former supporter was working for Senate Majority Leader Robert J. Dole, Gerald Ford’s running mate in the 1976 election in which Harris also competed.

He shouldn’t have been.

Populism is a historic feature of prairie states, from western Minnesota and the rise of its Democratic-Farmer-Labor party through parts of Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas to most of Oklahoma. It’s grown beyond geographic borders to demographics. The resentment of “big banks” and the eastern railroad companies grew as they pressured farmers to sell their lands, often at low prices, especially during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression. It’s part of our DNA. That resentment of banks and railroads has been replaced with Big Pharma, Big Tech, Big Media, and especially Big Government, among others (Big Food?). Especially at that agency Fred Harris wanted to abolish.

Just four years after co-chairing Harris’s campaign in my county, I would enthusiastically support another populist of sorts, Ronald Reagan. So did a lot of other Oklahomans who have now made the Sooner State a one-party state again. . . for Republicans.

Harris’s liberal populism defined the Democratic Party of his era, and much of his rhetoric, if not his ideas, were embraced by other Democrats running in 1972 (and since). While those ideas lost favor, the resentments fueling populism also began to shift during the Jimmy Carter Administration. Republican operatives like me began a studious, long-term effort to shed our “country club” moniker and win support from working-class Americans.

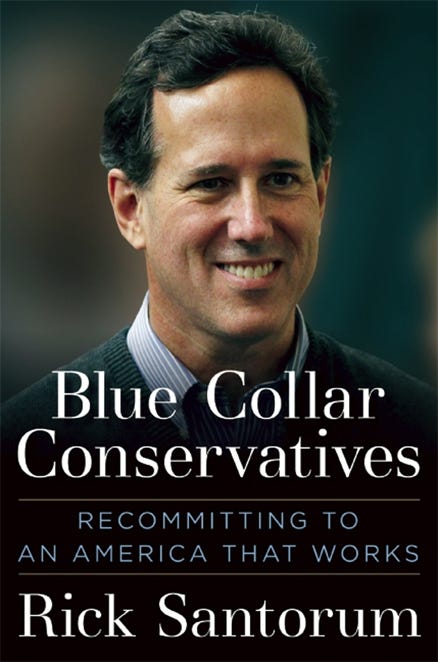

It took a while. Former US Sen. and two-time GOP presidential candidate Rick Santorum (R-PA) deserves credit as an intellectual father of the modern populist conservative moment, but Donald Trump is credited for cementing it. Trump based much of his 2016 campaign rhetoric on Santorum’s 2014 book, “Blue Collar Conservative.” You can ask Santorum.

“In the summer of 2014, Trump asked me to stop by his office the next time I was in Manhattan... When we walked into his office, he was sitting behind his desk holding a copy of my book Blue Collar Conservatives that I had published that spring. The first thing he said was, 'I read your book.'

I laughed. 'The hell you read my book.'

Trump shot back, 'I did; it was great!'

So I quizzed him on the message in my book – that the great middle of America was hollowing out as a result of big-government policies that were helping the elites but leaving blue-collar families behind. And to my great surprise, Trump passed my test with flying colors.

We discussed the problems facing Middle America – specifically the implications of unfettered globalization on America...

Harris was no fan of Trump, as he told Politico after the 2016 election.

When Harris looks at Donald Trump’s campaign, he sees a vision of populism fundamentally opposed to the way he saw the movement. In the 1970s, Harris aimed to build political clout by creating new coalitions across boundaries of race, gender and class, uniting people on the basis of their shared struggle.

“Populism is simply about voting for your own interests instead of against your interests—with the knowledge that your interests are the same as the interests of everyone else,” Harris says.

In electing Trump, Fred Harris believes the people voted against their own interests, choosing a man who will enrich himself and not them. He sees Trump as a leader who has built walls between groups and emphasized their differences in order to gain power—in fact, Harris isn’t so sure that the president-elect’s views can even be called populist.

“It really pisses me off when they talk about populists being racists, and calling George Wallace and Donald Trump populists,” Harris says. “Trump populism is really just demagoguery. It’s not my kind of populism.”

Like so many other Democrats, Harris got Trump emphatically wrong. Was Harris well enough in his final weeks to see the diverse coalition he could only dream of actually helping elect Trump? Trump won record support from Black and Hispanic men, younger voters, and especially non-college-educated “working class” voters. Entire counties along the Rio Grande Valley, each with Hispanic populations of 80 percent more, flipped dramatically for Trump in 2024. Harris’s birthplace and former hometown of Walters, Oklahoma, in Cotton County, bordering Texas along the Red River, gave Trump 84 percent of its vote.

That’s the coalition Harris wanted to assemble. Conversely, he’s seen his own party morph into an elite collection of college professors and wealthy, educated, mostly white urban and suburban liberals. While Trump succeeded where he failed, it’s fair to ask whether Harris unwittingly helped set the stage 50 years ago. RIP.

What an interesting story of important political and Oklahoma history.