Proportional Representation: An Answer to Gerrymandering?

If people want to feel represented in Congress, where they choose their representatives, rather than politicians picking their constituents, multi-member US House districts might be a solution.

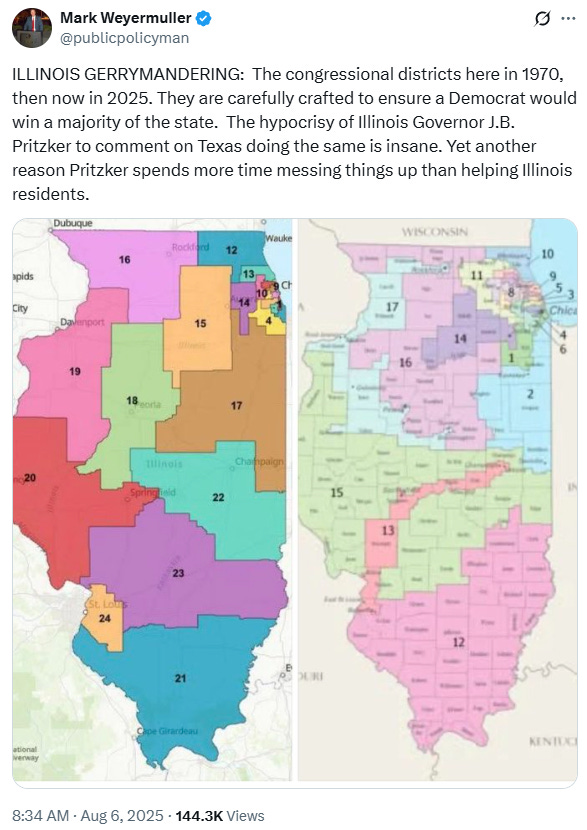

It’s tough, even painful, to watch the gerrymandering shenanigans underway in several states, including Texas. I didn’t like it when Democrats did it in places like California in 1981 or Illinois in 2021, and I don’t like Texas doing it now, but read on - the Biden Justice Department deserves a lot of credit.

I hate states like California even more for threatening to retaliate, fighting fire with fire, especially when they started the fire, with no regard to any consequence but one - the relentless acquisition of raw political power. Fighting fire with fire to insulate representation in Congress from the will of the people every two years by politicians picking voters, instead of the other way around, qualifies as a threat to democracy, even as it’s been going on since the beginning of the Republic.

But it is also a fact that the Biden Justice Department, in 2021 and 2023, successfully challenged the maps Texas came up with after the last Census for diluting minority voters. A look at the new 2025 maps shows that Texas fixed that problem by consolidating GOP-trending Hispanic voters, even as the US Supreme Court seems poised next year to eliminate racial considerations in gerrymandering redrawing districts. Be careful what you wish for.

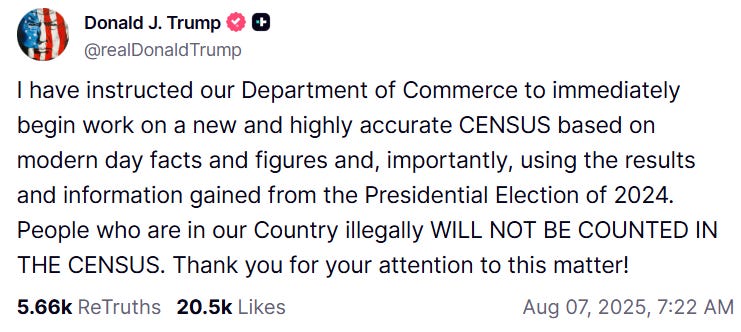

And now President Trump is throwing gasoline on the fire by “ordering” the Commerce Department to conduct a new census but not include illegal migrants for reapportionment purposes. The Constitution requires that everyone be counted, but it’s not clear if the President has the authority to exclude them from the process of redrawing congressional seats. Congress probably does, but the Supreme Court may ultimately have to weigh in, again.

Conducting a Census is expensive, costing anywhere from $13-16 billion, so Congress and its power of the purse (including purse strings) will be involved regardless. And I doubt it will qualify for expedited consideration under budget reconciliation rules (limited amendments and debate, simple majority passage in the Senate) since it’s not “mandatory” spending, but we’ll see. A census results in federal spending formulas that impact mandatory spending programs, so there’s that. It could wind up surviving a “Byrd bath.”

Trump issued a similar order when the pandemic-cursed 2020 Census was conducted, but Joe Biden, almost immediately upon being sworn in, quickly rescinded it in early 2021. And since somewhere between 10 and 20 million migrants have entered through the once-open, now-closed southern border, a new census is not without justification.

I’m also terribly unimpressed with the political theater by Democrats of fleeing their states to avoid doing their jobs. Ominously, perhaps, US Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) announced that the FBI will help track down absentee Texas legislators. Governor Greg Abbott is already moving to declare the seats of derelict Democrats vacant. I can think of better things for the FBI to do. I can also think of better things for Vice President JD Vance to do than traveling to state capitals to badger GOP governors and politicians to redraw districts when there’s nothing - no court order, no Justice Department decree - for them to do so.

Most states - those with more than one member (Wyoming, North and South Dakota, Delaware, Alaska, and Vermont each have one representative) typically redraw seats after a decennial census. But there’s nothing in the US Constitution or under federal law to prohibit them from redrawing lines every election if they want to. Some states restrict redistricting to every 10 years, including New Jersey and California, although Gov. Gavin Newsom is trying to find a workaround in retaliation for Texas. Many progressives, like most tyrants, find constitutions to be a nuisance to be worked around. The ends justify the means, someone once said.

And there’s no easy way around this sordid mess. The Constitution grants close to plenary powers to states to draw legislative district lines. Efforts to address the most egregious forms of gerrymandering, i.e., racial, are being undercut somewhat by courts backing off from intervening in redistricting. Democrats whine that plenty of blue states have “independent” commissions and are morally superior to power-grabbing Republicans in places like Texas, Oklahoma, and other red states. Those commissions are sometimes “nonpartisan” or “bipartisan” in name only, or still subject to partisan shenanigans. That’s laughable in most cases, of course, with just a cursory look at their gerrymandered states, especially Illinois, California, and much of the northeast.

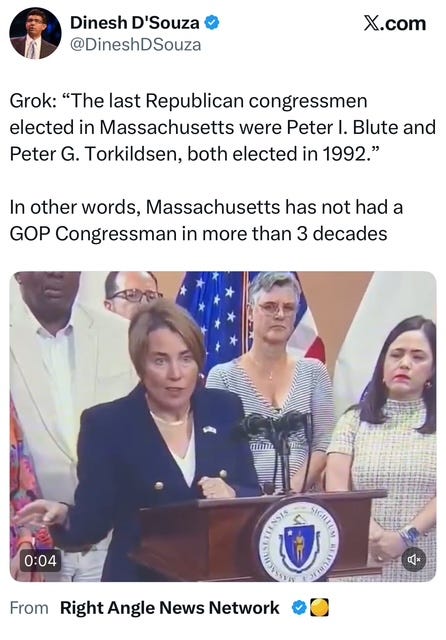

Hilarity ensued this week when Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey promised to reapportion the state's US House seats in retaliation for Texas. There’s a problem with that - they’ve already gerrymandered the GOP out of existence. The last GOP Representatives from Massachusetts were Peter Blute and Peter Torkildsen, who were both elected in 1992 and defeated for reelection in 1996 (by Reps. James McGovern and James Tierney, respectively), nearly 30 years ago.

GOP congressional candidates in Massachusetts only captured about 10 percent of the popular vote in 2024 and not even 10 percent of voter registrations (the vast majority of Massachusetts voters are registered independents). Still, then again, most of their seats are uncontested. GOP candidates for Governor have done better. President Trump captured 36 percent of the Bay State’s votes in 2024.

Another factor is that many of these blue states that have been drawing Republicans out of their seats have also been losing population. After the 1970 Census, Illinois had 24 seats. Now they have 17. They should explore why.

Performative art and political comedy aside, is there any way to address this unseemly behavior? In short, the only real way to do it is for voters to become sufficiently outraged to make it a top issue and replace offending legislators. But political power grabs, especially legal ones, rarely register in public opinion polls. Bread and butter issues like affordability, crime, and local problems have always reigned supreme, and probably always will.

But maybe it’s time to revisit the Apportionment Act of 1842, in which Congress, at the behest of the Whig Party (arguably the predecessor to today’s Republican Party), mandated single-member districts. Previously, as the nation was rapidly expanding westward and some states were struggling with electoral systems, some states featured “general tickets” or multi-member districts.

I’m not going to get into the political science weeds, but multi-member or “plural” districts are already a thing in some states. New Jersey is the example I’m most familiar with. They created single-member Senate districts, from which voters choose two members of the Assembly. All the candidates run together (not unlike today’s “jungle primaries” in California and, until recently, Louisiana), and the top two vote-getters win. More often than not, the top vote getters are of the same party, but not always. Arizona, South Dakota, and Washington State all employ plural districts.

Here’s the thing. States don’t, technically, have to reapportion seats. Once the Census establishes the number of congressional seats, if a state legislature is deadlocked and there’s no other way to carve up seats, then everyone runs statewide for the available seats. Apportioned seats can’t deviate very much from the established “average” district size for a state. And district populations can grow or shrink a lot over a decade. Seven states employed “at large” elections for the US House in the election of 1840. The Constitution doesn’t require any particular electoral procedure.

Gerrymandering, especially in high-population areas, can get very tricky. Counties and communities, and even neighborhoods, are divided to “make the numbers,” either the required population count or, more often than not, predicted partisan behavior.

Let’s be real. Repealing or replacing the Apportionment Act of 1842 (and its successor laws) is about as likely as you or me spontaneously combusting. But there’s nothing wrong with starting a debate on how to move past our current gerrymandering to a more sane and rational approach that might include proportional representation.

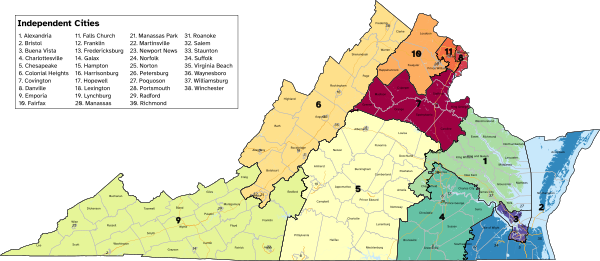

Here’s how it might work, using my environs of Northern Virginia as an example.

Virginia used two state Supreme Court-appointed “special masters” in 2021 to eventually craft a map the legislature couldn’t agree on, one representing each party. They did a pretty good job of keeping the districts contiguous and respectful of demographics and county lines (in most cases). Virginia has one of the fairest maps in the nation.

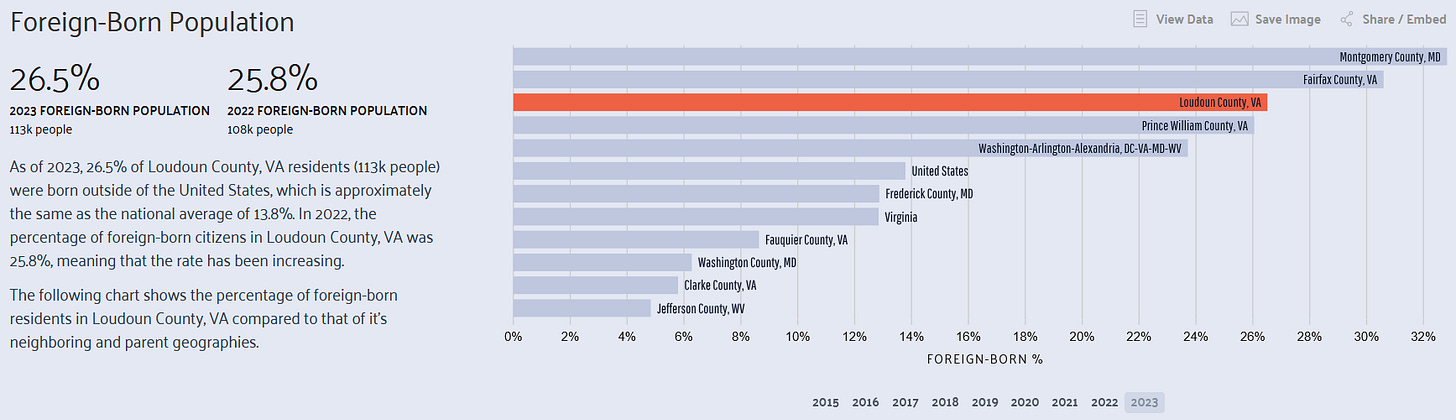

Northern Virginia features four congressional districts, including the 8th (D+26), consisting primarily of deep blue, bureaucrat rich Arlington and Alexandria; the 11th (D+18), encompassing the state’s largest county by population, Fairfax; the 10th (D+6), based in America’s wealthiest county, Loudoun, and home to 80 percent of the world’s internet traffic where 26 percent of the population is foreign born, and the expansive 7th (D+2), which takes in a few counties that are technically outside The Swamp’s Washington, DC’s orbit, but not by much. They are all represented by Democrats. Still, they have a great deal in common, including a media market (DC). You might be surprised how far many workers here commute to Washington and its close-in ‘burbs. The big government and contractor paychecks and job security make it worth the price.

Under one version of proportional representation, these four single-member districts could be combined into one multi-member district, where voters would elect the top four candidates. If Democrats win, say, 65 percent of the vote (which would be high, even for this area), they would win two-thirds of the districts, or three. Republicans, winning a third or more of the vote, would get one.

That would be one more Republican than the region has today. Finally, I would have a congressman who represents me, instead of the human ATMs who “represent” the area now.

This system works less for rural areas, which already take up considerable real estate. Even states like Oklahoma, with its blend of two distinct cities and mostly rural communities, multi-member districts wouldn’t make much sense. But for urban-suburban areas that share geodemographic interests and characteristics, it would work splendidly. Northern Virginia and other Democrats bent on power might feel differently.

It would work in Philadelphia’s collar counties of Delaware, Montgomery, and Bucks, possibly including Chester as well, which is also home to four districts. I suspect you would get the same outcome, with Democrats winning three seats and Republicans one, which is how it shakes out today, with Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) representing purplish Bucks County. I see it working in every major city and its suburbs, from Los Angeles to New York.

Proportional representation has its flaws, and Democrats will spot one right away - diluting their power after successfully gerrymandering the GOP out of seats in most blue or blue-ish areas. I would argue it strengthens the political clout of a particular geodemographic area by making it somewhat more bipartisan. But that’s just me. And because it doesn’t work everywhere, having a hybrid system of single- and multi-member districts could seem unfair or imbalanced, even if the one-person, one-vote principle is undisturbed. It complicates things.

Multi-member representatives could work together more effectively as a team to represent their area, leaving single-member districts at a disadvantage. “Minority” voters might feel represented and not shut out. I’m sure there are other factors, both pros and cons. The House Administration Committee would have to struggle with resources and staffing for multi-member vs. single-member districts, given the larger geographic areas and populations of the former. It might make campaigning more expensive, but it also might strengthen the role of parties, a good thing.

I admit that it may ultimately prove unworkable, if politically unpopular in some circles. And we know it’s not happening in the current political environment. Certainly not anytime soon, if ever. I’m realistic.

Friends of mine, including Mike Johnson and Jerry Climer, authors of the fabulous and definitive book on Washington, “Fixing Congress: Restoring Power to the People,” support increasing the size and membership of the US House to make it more available and responsive to everyday Americans. They make a strong case, pointing to the membership of Great Britain’s House of Commons (650), with not even a quarter of our population, and even tiny New Hampshire’s lower house, which has 400 seats (they also draw a base annual salary of $100, so there’s that). There’s no doubt that representing 200,000 constituents, as each House member did on average in 1913, was much easier and more effective than trying to represent 762,000 today.

It also might make it easier to draw district lines. But that likely won’t solve the gerrymandering problem. Getting to a more reasonable 250,000 persons per congressman would more than double the size of the US House to 885. Gulp! That would require a new Capitol megaplex building, since the current House chamber can seat, maybe, 650 for joint sessions with a few extra chairs tossed in, not to mention the added salaries, staff, and expenses. But they’re not advocating for that large a House.

During a joint session of Congress (think State of the Union Addresses), the House chamber accommodates the full House (435 voting members plus five non-voting delegates); 100 US Senators; nine Justices of the Supreme Court; eight members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; about 100-150 members of the “diplomatic corps;” and assorted legislative officers and select staff.

But perhaps we can agree on one thing: this mindless and destructive gerrymandering madness needs to stop. If this debate can help precipitate an alternative, all the better. Multi-member districts seem to work in the states where they’re being used. Let’s start the discussion.

Kelly, thanks for the blurb about Fixing Congress. My very biased view is that Mike Johnson and I do offer citizens some useful factual history and maybe more importantly, some creative ideas about how to FIX the mess.

Your other pieces in this post also deserve reader attention, especially the one about redistricting. We both know when redistricting became a quasi-scientific (mathematical) exercise that has done harm to effective democracy. I hope your piece, as well as our book, stimulates readers to offer ideas on how to address the challenge.

Why not make the delegations from each state at large, proportional to the statewide vote?

The major disadvantage is that it would eliminate independents and "maverick" candidates who could win in one area, but not statewide. Where would we be without the antics of a Jasmine Crocket, Lauren Bobert, or Hank Johnson? Even politics needs comic relief!

But it would guarantee the 30+% of voters in larger states a number of representatives closer to their own share of the population. And it would guarantee that each voter has at least some representative who could respond to their needs.

It would, alas, greatly increase the load of responsibility for each representative, but parties could assign individual members to parts of the state, so that in effect every region is represented by one D and one R. It would also diminish the local flavor of geographical districts to some extent, but there's no reason to suppose that the candidates would not be drawn from all areas of a state.

Not perfect, but what is?