Leave the Parliamentarian Alone

Blaming the Senate's Parliamentarian for problems with the "One Big Beautiful Bill" is misplaced. And the death threats need to stop.

If there’s one thing many congressional staffers don’t want, it’s media attention. That’s especially true if it involves controversy. And especially these days, with cancel culture lurking in the shadows.

Queue the Senate’s Parliamentarian of 13 years, Elizabeth McDonough. If you’re keeping up with the news about the “Big Beautiful Bill,” you’ve probably heard or read her name, and perhaps seen photographs like this.

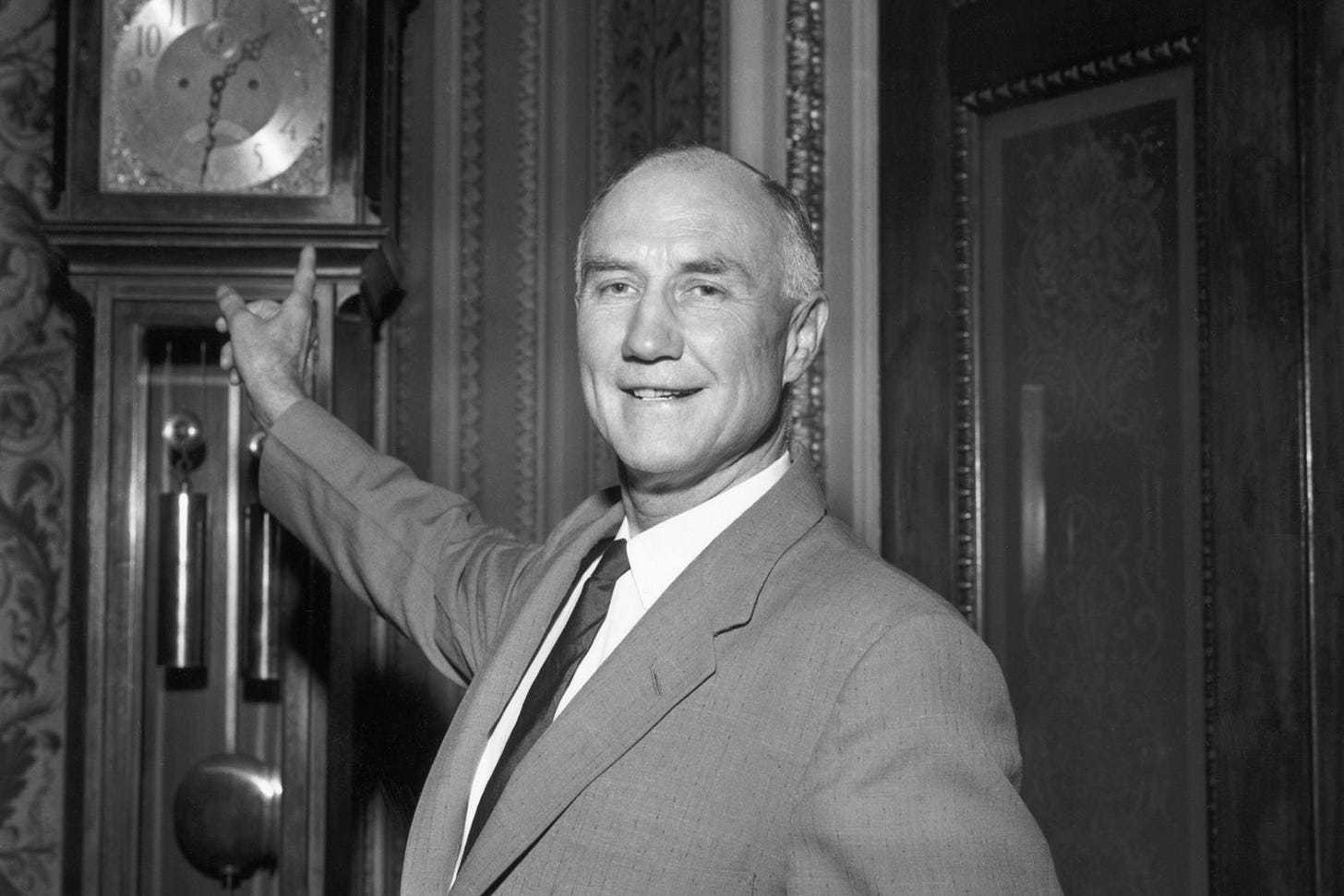

I know Elizabeth. I was Secretary of the Senate when she joined the Senate Library staff almost 30 years ago. After I left, she went to law school. Upon graduating and presumably passing the bar exam, she returned to the US Senate around 2002 as a junior staffer in the Senate Parliamentarian’s office, led by her mentor, Alan Frumin. When Frumin retired, she ascended to the role in 2012. Frumin was the Senior Assistant Parliamentarian when I was Secretary of the Senate; the late Bob Dove, the only Parliamentarian to be fired (twice) - was in his second tour of duty as the Senate’s Parliamentarian during my brief stint.

Dove was first fired by the late Senate Majority Leader Robert C. Byrd (D-WV), himself a Parliamentary and Senate Rules expert, when he disagreed with Dove’s “rulings.”

Side note: Parliamentarians don’t “rule.” They advise the presiding officer on parliamentary procedure. The presiding officer, whether it is the President of the Senate, Vice President JD Vance, or one of the newly elected Senators in the majority who are often relied on for one-hour shifts at the President’s desk, the highest point in the Senate Chamber.

Parliamentarians also offer a great deal of advice and counsel outside the Senate chamber. Senators and their staff who are writing legislation and want a bill referred to a specific committee, or to avoid multiple committee referrals, which is usually a kiss of death, will run drafts by the Parliamentarian to get their advice and counsel. Frumin was especially kind to me when, as a lobbyist, I would occasionally call to understand how specific bills I cared about were being referred to, such as the Agriculture Committee versus the Health and Human Services Committee.

But Parliamentarians really earn their salaries during the budget and reconciliation “season.”

Let’s briefly revisit the budget and reconciliation process, begging forgiveness for oversimplifying it. During one of its many post-Watergate reforms, congressional Democrats in 1974 enacted the Budget and Impoundment Control Act. It established a process that begins with the President submitting a proposed federal budget to Congress. Congress, under expedited procedures led by their respective budget committees, passes a joint resolution that establishes budget targets, including spending and tax targets. It is not subject to the Rule XXII Senate filibuster (a 3/5ths vote requirement to end debate). Debate is limited to 30 hours, although a “vote-a-rama” will occur if there are still several amendments pending after time has expired, at least in the Senate.

The budget is not sent to the White House for the President’s signature. It doesn’t have the “force of law.” It is a budget, after all, and nothing more. It doesn’t spend a dime or cut anyone’s taxes. But it does trigger the “reconciliation” process. That’s where the various authorizing committees produce tax and spending changes consistent with the budget. It usually results in just one reconciliation bill, but in past years, Congress has considered as many as four reconciliation bills. There was talk of two this year in the Senate - a tax bill, followed by spending reforms - until President Trump pushed for his “one big beautiful bill,” or the BBB (HR 1).

He wants it on his desk by July 4th, but that’s unlikely to happen, given the process the bill needs to go through, including a House-Senate conference committee to iron out differences between the respective versions arising from the House and Senate. It’s more likely to wind up on his desk in late July, before Congress adjourns for its traditional August recess.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the “Byrd Rule” that now dominates coverage of the Senate’s reconciliation process. Around 1985, after a decade of budget and reconciliation bills, Majority Leader Byrd became chagrined at the abuse of the reconciliation process to circumvent Senate rules and procedures, from the filibuster to policy issues and even committee jurisdiction. So, he won strong bipartisan support for a Senate rule change - the Byrd Rule - that strictly limits what can be included in a reconciliation bill. The New York Times has a nice top-line summary:

The House has no such rule, but they are wise to keep it in mind if they have hopes of seeing their version of the budget make it to the White House for the president’s signature.

As a result, when Senate authorizing committees begin to craft their individual reconciliation provisions, they go through a “Byrd bath” with the Senate’s parliamentarian, who acts as the chamber’s referee or umpire (pick your sport). The Senate majority aims to anticipate and avoid the possibility of a budget “point of order” that would require 60 votes—the filibuster threshold—to overturn it. With only 53 Republican seats in the Senate (plus the Vice President to break any tie votes), GOP members would need at least 7 Democrats to cross over with them, and that ain’t happening.

The Parliamentarian, with the help of her tiny team, must ascertain whether each provision is consistent with the Byrd Rule’s strict limit on consequential spending and tax issues, and whether it crosses a line into making “policy” decisions. The Parliamentarian advises Senators how he or she would advise the chair in the event a budget point of order is made against a particular provision. If no such point of order is made, then there’s nothing to rule on - it’s how some “policy” matters have made it through past reconciliation bills. The Parliamentarian relies on the plain reading of the Byrd rule text along with precedents made by her predecessors, including Frumin, Dove, and the late Floyd Riddick, author of “Riddick’s Procedure,” the definitive manual of Senate procedure and precedent.

In today’s deeply polarized and partisan Senate, there’s no more than one, maybe two Democratic Senators who might dare to do that, and rarely, depending on the issue. The reality is that congressional Democrats are too terrified of their Zohran Mamdani-AOC progressive base voters to cooperate with Republicans in any way. US Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA), is an occasional lone exception, especially on matters related to Israel.

Much is being made of reports that McDonough advised Senators that at least 15 provisions in the Senate’s BBB violate the Byrd rule. The include changes to the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly “food stamps”), Medicaid eligibility, and border security and enforcement (giving states more power), and selling off non-environmentally sensitive federal lands adjacent to growing cities to expand the housing supply.

The Parliamentarian hasn’t uttered a word publicly; all of this media coverage has come courtesy of Democrats, especially Senate Budget Committee Ranking Member Jeff Merkley (D-OR), via their websites. Conservative groups and others who are ignorant of the process and the role of the Parliamentarian went ballistic this week, inexplicably taking Democratic pronouncements as gospel. Here’s a good example from Eric Pratt, head of the Gun Owners of America - in a fundraising appeal, of course:

President Trump’s One Big, Beautiful Bill included critical pro-gun provisions that would have removed burdensome taxes and registration requirements on suppressors and short-barreled firearms. These measures are vital to protecting the hearing of law-abiding gun owners and ensuring your right to self-defense without government overreach.

But here’s the outrage…Senate Parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough, a partisan hack, has ruled against these provisions, stripping them from the bill under the guise of the so-called “Byrd Rule.”

Her actions are a direct assault on your Second Amendment rights, siding with anti-gun extremists who want to keep these common-sense protections out of reach.

This isn’t about Senate rules—it’s about MacDonough using her unelected position to push a radical anti-gun agenda. Senate Majority Leader John Thune has the power to fire MacDonough and restore these critical provisions, but he’s dragging his feet.

Since Thune won’t act, it’s time for VP J.D. Vance to utilize his position as president of the Senate to regain control. Once he does that, VP Vance can IGNORE Elizabeth MacDonough’s advice and ensure the NFA tax removal language are included in the One, Big, Beautiful Bill!

This is not only wrong and profoundly ignorant, but it is also dangerous and outrageous. It also might explain why McDonough is being doxxed on social media, including the publication of her home address and receiving death threats. I’m not blaming the GOA for them, but this vitriol doesn’t help. Sadly, the GOA isn’t the only one. And at least two Senators, Tommy Tuberville (R-AL, who is running for Governor) and Roger Marshall (R-KS), have called for McDonough to be fired.

Just like some Democrats called for McDonough to be fired when their Inflation Reduction Act provisions to raise the minimum wage and provide a path to citizenship for illegal aliens were found to violate the Byrd Rule.

You’ll note that the Republicans consulting McDonough aren’t talking, either. They’re going back to the drawing board to revise their language. At the time of this writing, at least one case that was previously found to be in violation now passes muster. Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) is also catching grief for saying he won’t try to overrule the Parliamentarian.

Good for the Leader. It’s the right call. And GOP Senators are wise to keep their powder dry and meet their spending reduction targets in other ways. They’re working on that now. In some cases, it may prove impossible, especially a House provision designed to curb nationwide injunctions from rogue federal judges, a matter that is now moot, thanks to a 6-3 Supreme Court decision in Trump v. Casa.

Can Thune fire the Parliamentarian? Of course, he can. Can Vice President JD Vance or another presiding officer ignore the advice from the Parliamentarian and rule the way he or she wants?

Yes, and Vice Presidents have done that before, going back to 1957 when Vice President Richard Nixon attempted to rule that the Senate’s filibuster rule was unconstitutional, as a new Congress hadn’t re-adopted the rule. Then-Parliamentarian Floyd Riddick, in his oral history of the Senate, indicated that he advised against that. Vice Presidents Hubert Humphrey (1969) and Nelson Rockefeller (1975) tried similar efforts. In Nixon’s case, the Eisenhower Administration was trying to get the Civil Rights Act through the Senate (they were unsuccessful, thanks to southern Democratic opposition, including a record-breaking 24-hour, 18-minute filibuster by the late Strom Thurmond (R-SC).

But what happened to those rulings (some say advisory opinions) from the chair? They were tabled or overruled by a majority of the US Senate.

It is essential to understand that 51 Senators - a simple majority - can do as they please. They can use the nuclear option to end the filibuster for executive and judicial nominations (and they did, first in 2013 and again later in 2017). But . . .

Say Merkley moves a point of order against a provision of the BBB once it hits the Senate floor this weekend or next week. Say McDonough turns from her chair on the dias, looks up to a smiling JD Vance, and advises him to rule in Merkley’s favor. Say Vance rules against Merkley. Can he do that? Yes. However, Merkley would then move to overturn the chair's ruling. And he might win. There’s a very good chance that there are not only 47 Democratic votes, but 4 GOP votes in support of the parliamentarian. I’ll let you guess who they might be.

Yes, the parliamentarian is a member of the Senate staff. They serve at the pleasure of the Majority Leader (and, technically, the Secretary of the Senate). He or she has no extraordinary power, beyond their evident expertise. Their advice and counsel can be ignored. But for the Senate to function, it needs an umpire to help it navigate the legislative jungle. And I can’t say this enough - fifty-one Senators can do as they please. If Vance has 51 Senators behind him to sustain a point of order, 51 Senators get their way. That’s how the place works.

I suspect Leader Thune knows that he does not have 51 votes to “overrule” the Parliamentarian on the BBB. The former “whip” knows his conference and how to count votes.

I have no idea what Elizabeth McDonough’s politics are, and frankly, I don’t care. I do care that she follows, carefully and strictly interprets, and enforces Senate rules and procedures. Why do you think only a couple of GOP Senators have called for her resignation? Other stalwart conservatives, including Sens. John Kennedy (R-LA) and Eric Schmitt (R-MO), have expressed support and confidence that they will revise provisions that will pass muster.

If you don’t like McDonough’s judgments, don’t blame her. Blame the late Senate Majority Leader Robert C. Byrd and the Senators who unanimously enacted the Byrd Rule. And be grateful that the Senate Democrats, four years ago, didn’t run roughshod over the process the way irresponsible and short-sighted conservatives are now demanding. Be careful what you wish for.

The Senate is dysfunctional enough without blowing up the Byrd Rule and further eroding the filibuster.

Great description of what is going on. Nixon's move in 1958 was a gutsy attempt to end the filibuster by Southern Democrats against Eisenhower's Civil Rights Act. Ultimately, Nixon succeeded. Nixon ended his threat to adjourn the Senate and reconvene it with new rules (sans the filibuster) in exchange for LBJ, then the majority leader, agreeing to end the filibuster. However, LBJ then insisted on Rule V, which stipulates that the Senate remains the only legislature in perpetual session. Thus, preventing future VPs like Nixon from ending the filibuster through a simple rules change. At the beginning of a session, the Rules can be passed by a simple majority. However, changing the rules mid-term requires a 2/3 vote to end a filibuster—the only exception to the 60-vote cloture rule.

Thanks for summarizing Parliamentary Rule lesson #101. Too bad some Members and staff haven't bothered to get a briefing on the background of the Rule and Byrd.