How Senators Choose Their Leader: Part II

Senators look for leaders they can trust to protect and promote them politically, who know the rules, and who will defend the Institution. External politics matter, but not how you think.

Find Part I here.

Sometimes, the best way to make a point is to walk through history.

Everett Dirksen (R-IL) was the first Republican leader I vaguely remember as I began to pay attention to politics around age 10. He died following complications from lung cancer surgery in 1969 and was succeeded by Hugh Scott (R-PA). Scott’s ascension, the GOP “whip” and second-in-command, wasn’t automatic. No one’s election is taken for granted, despite appearances.

In fact, “open seat” leader elections are very competitive. These opportunities don’t come very often. It helps to be in the right place at the right time. Even if you didn’t plan to seek the job.

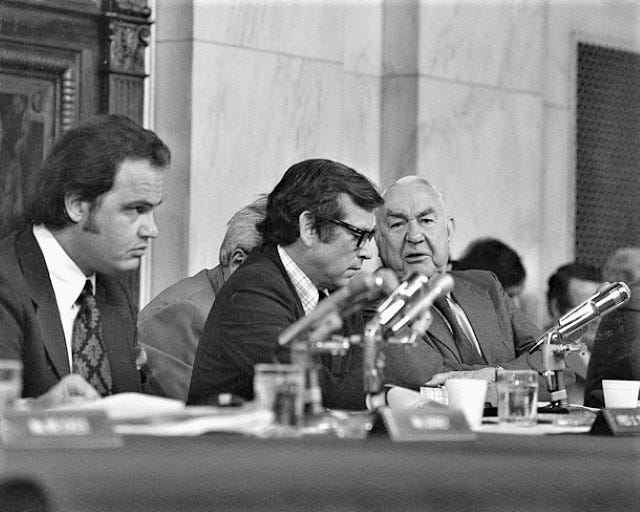

Scott retired in 1976 and was replaced by Dirksen’s ambitious son-in-law, Howard Baker. Scott had narrowly defeated Baker twice in previous leadership elections. Baker, elected in 1966, became famous for his even-handed and inquisitive role during the 1973-74 Watergate hearings, serving as the ranking Republican on a Special Committee chaired by the legendary Sam Ervin (D-NC). Baker coined the famous question, “What did the President (Nixon) know, and when did he know it?”

I must delve into the history and politics of how Baker was selected for the assignment, which had to be wrought with challenges. Was it a trap set by Hugh Scott? Baker may have thought, should he automatically defend his President, as Democrats behave today toward Biden’s scandals, or do the right thing and follow the facts wherever they lead? Did Nixon okay Baker’s ascension as the ranking Republican on a committee holding hearings that gripped the nation? Baker’s integrity was on national display. He played it straight and became a national hero.

Nixon, in 1971, offered a vacant seat on the Supreme Court to Baker, who took too long to decide. The impatient Nixon chose William Rehnquist instead. Another case of indecision qualifying as a decision. And a very consequential one.

With Hugh Scott’s retirement in 1976, Baker won the leader’s post by one vote over Michigan’s Bob Griffin. Baker would unsuccessfully seek the 1980 GOP presidential nomination from his Senate perch as Minority Leader, but with Reagan’s electoral landslide, found himself as Majority Leader in 1981. He served in that role for three years, helping advance Reagan’s first-term agenda, before Bob Dole ascended and led his party for nearly 12 years. Following the Iran-Contra scandal, Baker would return to politics in 1987 as Ronald Reagan’s last Chief of Staff. He died in 2014.

History instructs. Hugh Scott was narrowly chosen over his predecessor’s son-in-law. Baker was chosen, by one vote, over another veteran colleague. In 1984, Dole defeated the late Ted Stevens (R-AK), Baker’s whip and second in command, by a whopping three votes. Dole had been chair of the Senate Republican Conference, leap-frogging Stevens. Three other candidates were eliminated in earlier balloting, including the estimable Richard Lugar (R-IN) and Pete Domenici (R-NM).

The New York Times, on November 29, 1984, writing about Dole’s election reveals much about Senators' thinking when choosing a leader.

The Senate majority leader is one of the most influential figures in Washington. Inside the Capitol, he sets the Senate agenda, decides what bills come to the floor and negotiates compromises with House Democrats. Outside the Capitol, he speaks for the Senate to the White House and, through news organizations, to the public.

Many senators said they had picked Mr. Dole because of his ability to perform these functions. ''In the ultimate analysis,'' said Senator Slade Gorton of Washington, ''we picked the individual with the most experience in managing bills on the floor. He is also the best public speaker.''

In an interview, Mr. Dole stressed two basic facts of political life that will place limits on the White House and the Senate leadership: Democrats control the House by a wide margin, and 22 Republican Senators face re-election in two years. ''It's tough up here,'' the new majority leader said. ''And it will be tough for the next few years.”

Managing legislation on the Senate floor. Negotiating with opposition. A powerful messenger and speaker. Politically astute and influential. Protecting colleague’s interests. The article discussed Dole helping Reagan with his agenda, but the Senate and his colleagues would come first.

Some things never change. Until they do.

Fast forward to 2000. Trent Lott (R-MS) succeeded Dole upon his resignation in 1996 with a 55-seat GOP majority. He saw the GOP’s majority whittled to zero - a 50/50 Senate with only incoming Republican Vice President Dick Cheney breaking the tie - thanks to a disastrous 2000 election cycle. One Senator, Georgia’s popular Paul Coverdell, died. Four other colleagues, including Lott’s close friend, Slate Gorton (R-WA), were defeated for reelection.

On December 5, 2002, the GOP had just recaptured the majority with a one-seat margin, with second-term Republican and heart-lung transplant surgeon Bill Frist (R-TN) at the helm of its official campaign arm, the National Republican Senatorial Committee. As the holiday season began, retiring Senator Strom Thurmond was feted for his 100th birthday in the Dirksen Building. Thurmond and I became close during my tenure at the National Republican Senatorial Committee when I helped supervise his 1990 reelection and again as Secretary of the Senate five years later. Thurmond was ending his legendary Senate career that year to be replaced by Lindsey Graham (R-SC).

I loved Thurmond’s stories, especially about the 1948 presidential election, in which he ran as a “Dixiecrat.” Governor of South Carolina at the time, he carried several southern states, including Lott’s home state of Mississippi. At the time, Thurmond was both a Democrat and a segregationist, as were most southern Governors, Senators and politicians. Thurmond became a US Senator in 1954, the first Member of Congress elected on a write-in vote. I was honored to be included with the Senate delegation in 2003 to attend Thurmond’s funeral in Columbia, South Carolina. The trip was led, and the eulogy was delivered by US Sen. Joe Biden (D-DE).

Someday, I’ll tell the story Thurmond told me while we were in North Carolina stumping on behalf of Jesse Helms’ 1990 reelection, how close he came to being President after the 1948 election.

Thurmond long ago disavowed his past on race and civil rights issues (he still holds the record for the longest filibuster in US Senator history, 24 hours and 18 minutes, on the 1957 Civil Rights bill) and became a Republican in 1964. Much of that past had been forgotten until December 5, 2002. Sen. Lott, in his book “Herding Cats,” painfully recalls the story.

At Thurmond’s event, Lott followed his Senate leadership predecessor, Bob Dole, who had used many of the same Thurmond quips Lott had planned to deliver (his staff should have known that would happen). Left with less to say but wanting to make an impression as least as good as Dole’s, he went off the cuff. “I want to say this about my state. When Strom Thurmond ran for President, Mississippians voted for him. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn’t have had all these problems over the years, either.” He said he was trying to compliment an old friend on his birthday. Thurmond passed away six months later.

As Lott notes in his book, PBS’s Gwen Ifill aired the quote and asked what he meant by that. After all, Thurmond’s 1948 campaign was based on racial segregation.

It took a while for Lott’s intended compliment to get out and sink in, but Lott became one of the first victims of cancel culture in the internet age. The media firestorm resulted in rumors of intrigue between the Bush White House and GOP Senators. Over the following three weeks, with the controversy not abating, GOP Senators began to doubt Lott’s ability to lead the GOP in the Senate, and with it, help carry Bush’s agenda into the 2004 reelection campaign. Outreach to minority voters was a priority for Bush’s campaign team. Republicans, long the party of civil rights, were sensitive to accusations of racism from the party of slavery, the Ku Klux Klan, and Jim Crow (Democrats). They still are.

Nobody believed, and there was never any evidence that Lott held racist sympathies, but damage was being done to the GOP brand. After all, Democrat then, and even now, claim that Democratic “crackers” of yesteryear just switched parties, and that the South never really changed. That’s stupid and ignorant, but no matter.

Eventually, my former boss, then-Assistant Leader Sen. Don Nickles (R-OK), issued a statement calling for Lott to be replaced with a candidate who could unify the caucus. It broke the dam of support protecting Lott, who continued to enjoy strong support from his closest colleagues, including Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and Rick Santorum (R-PA). Finally, Sen. Frist, the marathon runner on whose successful 1994 campaign I worked, agreed to step up and serve.

Lott blames Frist and White House aides for Frist’s “power grab” during the Holiday season. Lott eventually stepped down. “Democrats tend to surround their wounded players and try to prop them up, but we Republicans eat our own. It’s not sour grapes; it’s just the way it is,” Lott said in Herding Cats.

He’s not wrong, but it was a little more complicated. These things don’t culminate overnight, even by surprise.

A general observation: Those who connive are the first to accuse others of conniving. “Projection” is a tactic used by those who use the tools and weapons being projected. No disrespect intended. It’s not sour grapes; it’s just how it is.

By his admission, Lott was willing to “roll” his GOP colleagues to “get things done,” which often comes at a price. But the conference’s deliberations were a cold calculation. Something had to be done. Frist was popular with his colleagues and a growing national celebrity for his actions following a tragic shooting at the Capitol in 2008, where he saved the life of a wounded, deranged shooter. Frist also took charge after a serious 2001 anthrax outbreak via mail delivered to the senate office of Sen. Tom Daschle (D-SD).

Frist organized the Senate’s Anthrax response and dispensed Cipro tablets, a powerful broad specrum anti-biotic, to minimize any injury from the terror attack. He calmed nerves and assured a nervous Capitol Hill. At the time, he was the only doctor elected to the Senate. He made himself available to anyone he knew, including my family, for medical advice and assistance.

In his 2009 book, “A Heart to Serve,” Frist denies any skullduggery in replacing Lott. “The controversy was exactly what the Republicans didn’t need,” he wrote.

In his book (chapter 11), Frist details how he became Senate GOP leader. Don Nickles called him and said he, Nickles, didn’t have the votes to become leader. In a biography on Nickles, he claims he never tested the waters. Nickles had already announced plans not to run for leader - he was term-limited as whip - and assume the chairmanship of the Senate Budget Committee and finish his term. Nickles retired after the 2004 election.

“You should be majority leader,” Nickles told Frist, which he described as dropping “a real bomb.” “You have the support, you don’t have any negatives, and you have the positives. You are the kind of image we need right now.” Frist claims he had no designs on the leader’s role. He wasn’t so sure he wanted the job.

Frist claims that the mood changed in the Conference after President Bush criticized Lott for his Thurmond birthday comments at a speech in Philadelphia. Bush otherwise did not personally interfere (White House staff may be another matter) with the Senate GOP Conference’s deliberations. As many thought or hoped, things were not blowing over or getting better. Sentiment evolved, and finally, a choice for a new leader boiled down to incoming Assistant Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), Conference Chair Rick Santorum (R-PA), or Dr. Frist. McConnell and Santorum knew how to count. Frist had the votes.

Santorum set up a Senate GOP Conference call for December 23rd, two days before Christmas, three days after Lott officially withdrew. Senator John Warner (R-VA) asked to read the “physician’s prayer” before the roll call was completed. Lott read a statement of contrition and left the call. Frist’s was the only nomination put forth. It was unanimous. It remains the only GOP leadership election I know that was conducted by telephone.

Frist and his election broke the mold in many respects, but the circumstances were unique. He never aspired to the job, but destiny came calling. He’d been in the Senate only eight years, with just two years on the lowest rung of the leadership ladder. He didn’t know the rules as well as McConnell and others and wasn’t initially a strong floor leader. But immensely likable, charismatic, brilliant, energetic, a quick study, and cautious yet confident, he grew quickly into the role. McConnell proved a strong and supportive understudy. When Frist kept his campaign promise not to serve more than two terms, McConnell easily moved into the leader’s job, in 2007, which he had held since.

With McConnell’s tenure and the likely candidacy of two or three senior leadership members to succeed him come Fall, some say the Senate GOP conference has reverted to the historical norm in choosing a leader. We’ll see. There are about 17 members of the conference - and possibly more to come in November - who may want to usher in a more aggressive, even combative leader to “shake things up.” History shows that many Senators itch for that but usually fall short of a majority, often encountering resistance among their colleagues, often over institutional concerns.

A Leader’s job isn’t to advance his or her agenda but to advance those of his colleagues, including advancing their legislative agenda and winning and keeping a majority. That separates the leadership from many other policy and politically-driven US Senators, who tend to lack patience and collaborative leadership skills for the job.

What are senators looking for today? It depends on individual Senators and their agendas, but no doubt they want someone who listens well, who they can trust, and who excels at the internal (managing the legislative agenda) and external (managing the political landscape) while unifying the caucus. It helps a lot if they like them. That’s a tall order, especially when many circumstances are out of your control. Agenda-driven senators will never be happy unless you embrace their agenda en toto.

Each Senator will do a walk-through of history with each candidate, figure out what kind of leader they will be, and how they will decisively yet collaboratively drive the bus, hopefully not off a cliff. Judgment, demeanor, personality, and social sensitivity will all play in. And the role of spouses cannot be underestimated. They often get the first and last words.

Committee chairmanships, political optics, campaign support and help, media relationships, policy considerations, legislative history, and accomplishments will drive the process.

“The Senate is a different kind of place,” Frist writes in A Heart to Serve. “The Founders designed it to be one set removed from the passions of the American people.

“The very nature of the Senate caucus is to resist outside influences and forces, even those that might come from the White House,” he adds. “And for leadership selection within the body, the complicated personalities, fierce loyalties, and the deferential respect for the institution and its traditions play a much larger role than outsiders might imagine.”

A walk through the Senate’s history makes that very clear. As they emerge, I’ll have more to say about the candidates for leadership positions. Buckle up.

“What really makes the Senate work--as our heroes knew profoundly--is an understanding of human nature, an appreciation of the hearts as well as the minds, the frailties as well as the strengths, of one's colleagues and one's constituents.” - former Senator Howard Baker, July 17, 1998.

Wow. What a great history and explanation of the Senate's not-always-formal processes for picking a leader. My boss and I arrived in the Senate just in time for the election of Bill Frist. Our office was next door to Senator Lott, and he frequently stopped by to talk with Senator Talent. Interesting times, indeed.