Has Your University Signed "The Chicago Statement?"

The University of Oklahoma and entire University of Texas system have just joined 91 others. Why haven't more? What happens on campuses infects the culture at large.

Vietnam War-inspired protests were all but gone on campuses when I started college in 1974, but the “free speech” movement they spawned was just getting started.

It’s no secret that this college-anchored free speech movement has evolved since the early 1980s, when “free speech zones” were established on campus grounds. But free speech advocates soon began to challenge them as too restrictive. From Middle Tennessee State University’s Free Speech Center:

Many First Amendment advocacy groups, such as the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), believe free-speech zones on campuses are unconstitutional, and several groups, as well as university students themselves, have challenged free-speech zone policies both in and out of court with mostly successful results.

In 2000 the New Mexico chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and two New Mexico State University students filed suit, challenging that school’s free-speech zone policy. The university settled out of court and revised its policy, so that all outdoor areas generally accessible to the public can be used for petitioning, protesting, and related activities.

In June 2002, students and faculty at West Virginia University filed suit against that school, alleging that its free-speech zone policy, which designated seven small areas making up less than 5 percent of the total campus as free-speech zones, was unconstitutional. By December 2002, the university had abandoned the policy.

The Supreme Court recognized in 1981 (Widmar vs. Vincent) “that the campus of a public university, at least for its students, possesses many of the characteristics of a public forum.”

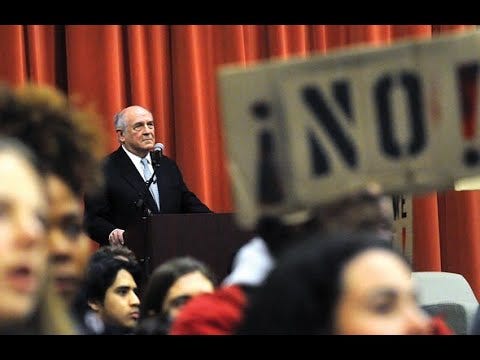

But over the past decade, the trend abruptly changed - speech and speakers were canceled and even assaulted for wrongthink. In 2017, political scientist and author Charles Murray was infamously protested, harassed, and attacked at Middlebury College in Vermont. A female professor suffered a concussion.

Professor Bret Weinstein, who refers to himself as “deeply progressive,” was hounded off campus that same year at Evergreen State College in Portland, Oregon. Weinstein triggered woke students when he challenged the premise of “absence day,” where white people weren’t allowed to appear at college.

Weinstein explained, “there's a huge difference between absenting yourself to make a point, which I support and absenting other people based on their skin color, which I will never support. What's more, it is surely illegal on a public campus in 2019 in the United States.” The college’s enrollment soon tanked after their social justice meltdown. Weinstein teaches elsewhere and has built quite a following.

These are but two of many incidents on college campuses where speakers were canceled or, worse, by woke mobs.

And it extends to corporate campuses, too. After the 2016 election, I invited former Senator and presidential candidate Rick Santorum (R-PA) to my employer’s headquarters in New Jersey (I was Vice President of Government Affairs) for a town hall with interested employees (attendance was voluntary). I routinely hosted voluntary town halls with members of Congress and other public officials representing both major political parties and diverse views, and never had an issue with colleagues upset over choices of speakers. Having seen Santorum and former Vermont Governor (a former Democratic presidential candidate) Howard Dean discuss the 2016 elections at a post-election conference in Canada, I thought Santorum would provide valuable insights on that year’s presidential election, which Donald Trump surprisingly won (Trump defeated Santorum and a dozen other GOP candidates for the nomination). The primarily Canadian audience was largely mesmerized by Santorum’s and Dean’s insightful analysis of an election south of their border they found hard to grasp.

But a small and noisy woke mob at my workplace wasn’t as intellectually curious. They selectively excavated controversial comments made by Santorum over his career (out of context, primarily) to pressure our head of human resources and, eventually, the CEO to cancel my event.

I was told that there was no such thing as “free speech” at my now-former employer. True enough. I persisted in inviting Santorum to a private lunch at the company with a dozen employees who were upset over the cancelation. The Senator, a personal friend, was surprised but took it all in stride. He’d been through worse. The lunch was a massive hit for those lucky enough to attend.

No, corporate campuses are not public fora like colleges and universities, but please remind me of the purpose of “diversity and inclusion” programs that proliferate in the corporate world. And many corporations have no problem weighing in on issues that have nothing to do with their products, services, or purpose. Trends on college campuses have infected the culture at large, including workplaces, and not always in a good way. Perhaps some “diversity” and “inclusion” cultures are more equal than others, to borrow from George Orwell.

And then you have companies who censor “misinformation” - violation of groupthink - on behalf of government and political actors. The Twitter Files, anyone?

So perhaps it was inevitable that the University of Chicago, spotting this censorship and cancellation trend two years earlier, established a “Committee on Freedom of Expression.” It was created “in light of recent events nationwide that have tested institutional commitments to free and open discourse.” Led by law professor Geoffrey Stone and including distinguished academicians from several fields, in July 2014, it produced a three-page report known now as “The Chicago Statement,” now subscribed to by 93 colleges and university systems. Two key paragraphs:

Of course, the ideas of different members of the University community will often and quite naturally conflict. But it is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive. Although the University greatly values civility, and although all members of the University community share in the responsibility for maintaining a climate of mutual respect, concerns about civility and mutual respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas, however offensive or disagreeable those ideas may be to some members of our community. (Emphasis added)

The freedom to debate and discuss the merits of competing ideas does not, of course, mean that individuals may say whatever they wish, wherever they wish. The University may restrict expression that violates the law, that falsely defames a specific individual, that constitutes a genuine threat or harassment, that unjustifiably invades substantial privacy or confidentiality interests, or that is otherwise directly incompatible with the functioning of the University. In addition, the University may reasonably regulate the time, place, and manner of expression to ensure that it does not disrupt the ordinary activities of the University. But these are narrow exceptions to the general principle of freedom of expression, and it is vitally important that these exceptions never be used in a manner that is inconsistent with the University’s commitment to a completely free and open discussion of ideas.

Princeton became the first university to ascribe to The Chicago Statement in April 2015. Purdue University, led by former Indiana GOP Gov. Mitch Daniels, quickly followed suit. By the end of that year, nine schools had signed on.

But just because schools have signed doesn’t mean they’re living up to it. Take Georgetown University, for example, where I once attended graduate school. We’ll let Ilya Shapiro, a constitutional and legal scholar now with the Manhattan Institute, tell his story:

In late January, when news of Justice Stephen Breyer’s retirement broke, I tweeted in opposition to President Biden’s decision to limit his nominee pool by race and sex. I argued that Sri Srinivasan, the chief judge of the federal appellate court based in D.C.—who also happens to be an Indian-American immigrant—was the best candidate, meaning that everyone else was less qualified. So if Biden kept his promise, he would pick what, given Twitter’s character limit, I characterized as a “lesser black woman.” Then I went to bed.

Overnight, a fire storm erupted on social media. I deleted the tweet and apologized for my inartful choice of words, but stood by my view that Mr. Biden should have considered “all possible nominees,” as 76% of Americans agreed in an ABC News poll. (I stand by that view to this day.) But it was too late. My ideological opponents were out for blood, or at least my new job—even before I was due to assume it on Feb. 1.

Shapiro’s new job was to have been executive director for the Center for the Constitution at Georgetown University Law School. An investigation ensued. More from Shapiro:

It’s become clear now that the investigation, led by human resources and the office with the Orwellian title of Institutional Diversity, Equity and Affirmative Action (IDEAA), was a sham. And that the process was the punishment. On June 2, about a week after the semester ended and students left campus, I was reinstated on the technicality that I hadn’t been an employee when I tweeted and so wasn’t subject to discipline under the relevant policies.

I celebrated that technical victory in the pages of Wall Street Journal, but further consideration showed that Georgetown had made it impossible to fulfill the duties I had been hired to perform. After full analysis of the IDEAA report that hit my email inbox later that afternoon, and after consultation with my lawyer and trusted advisers, most notably my wife—a better lawyer than all of us—I concluded that remaining in that job was untenable.

This is cancel culture, a violent escalation of censorship. Perhaps the University of Chicago, or an allied non-profit, could be assigned to hold signatories accountable, so it’s not just a meaningless virtue signal.

Even after 234 years since the First Amendment was ratified as part of our Constitution, freedom of speech remains a work in progress and under assault. Only 93 universities or university systems have signed on to The Chicago Statement out of nearly 4,000 higher education institutions in the United States, which disappoints and troubles me. I’m puzzled why my sons’ alma maters are missing, Elon University (NC) and Bucknell University (PA). And why isn’t my alma mater listed (the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma)? Perhaps I will rectify that.

You can find where a university falls on FIRE’s free speech rankings here. Not surprisingly, the University of Chicago ranks first. Purdue ranks third, behind Kansas State. Mississippi State and Oklahoma State round out the top five. Bucknell ranks 48th. Not all schools are ranked, including Elon. Oddly, Hillsdale University, a classical Christian school that famously eschews government funding, is dinged for “policies that clearly and consistently state that it prioritizes other values over a commitment to freedom of speech.” They are one of five schools excluded from the overall rankings, despite being listed as “slightly above average.” Hillsdale hasn’t signed on to The Chicago Statement, either. I need to find out why. Hillsdale certainly entertains speakers who aggressively defend free speech.

It concerns me that schools with a religious bent may be somewhat disadvantaged by FIRE’s rankings. Religious freedom is not inconsistent with free speech. They share the First Amendment, among other rights that go hand in hand, including freedom of the press, freedom of association, and your right to petition the government. Shall I include the second and subsequent amendments?

“I do not understand why many academics have supported or stayed silent as our faculties have become intellectual echo chambers,” says George Washington University law professor and criminal defense attorney Jonathan Turley, himself a University of Chicago graduate. “However, it is depriving our students of the type of diverse and vibrant intellectual environment that many of us enjoyed as undergraduates.”

Is your alma mater among the 93? If not, perhaps you can rectify that, too. Then hold them accountable. And if the First Amendment remains under assault after 234 years, so are you and all your rights.

The free speech movement was started mainly by liberals after attempts to stop left-wing speakers form voicing opinions on college campuses and elsewhere. Now much of the threat to free speech comes from the left. Time for all of us across the political landscape to get into our dis-comfort zones and support the University of Chicago statement.