Do Republicans Need Another "Contract With America?"

Some conservatives are attacking Sen. GOP leader Mitch McConnell for eschewing a legislative agenda for the 2022 mid-term elections. Who's right?

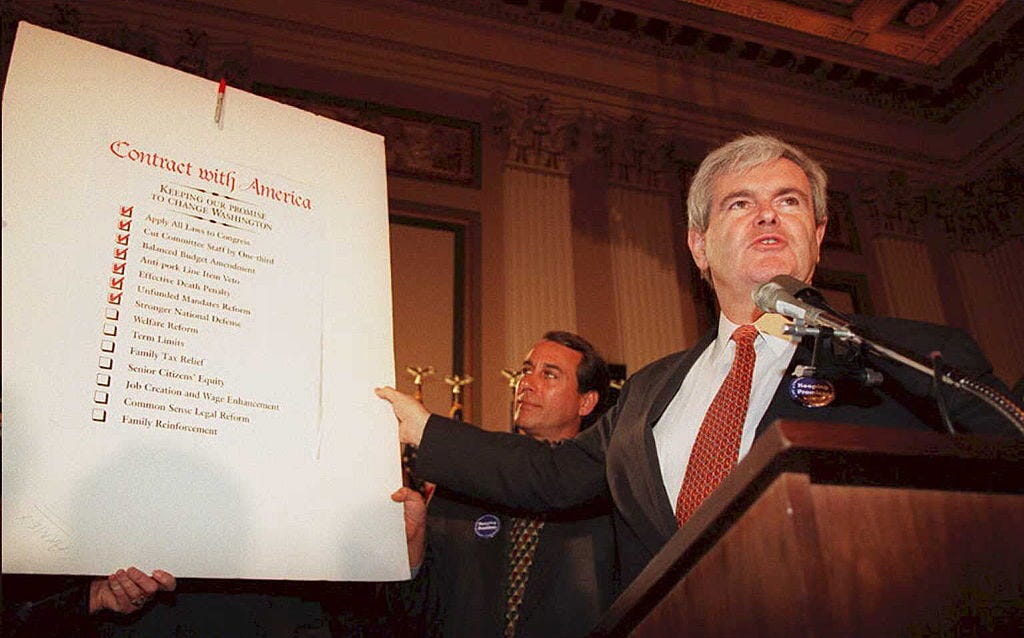

Amidst debates among Republicans, such as the extent to which the U.S. should support and defend Ukraine, this has emerged: Do congressional Republicans need a positive, pro-active agenda to run on for the 2022 midterms? You know, like the 1994 Contract With America? Will it help? Is it politically necessary?

In December, House GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) said he and his caucus is rolling out a “Commitment to America” over the year. It has already started with a “Parental Bill of Rights,” queuing off Governor Glenn Youngkin’s success with the issue of education with voters in the 2021 Virginia elections.

Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell was asked by reporters if his Conference would follow suit with a unifying legislative plan for the 2022 mid-terms as part of a strategy to capture a majority. “I’ll let you know when I take it back,” he said. Some conservatives are not happy.

Axios reported on the leaked details of a private dinner in early December involving Senators up for reelection in 2022 and major donors.

A donor asked a question that could only be answered by McConnell. According to a source in the room, the donor said something to the effect of: We all know what's wrong with the Democrats, but what are we going to be running on to help us win?

McConnell's response was something to the effect of, With all respect, that's not what we're doing, the source said.

McConnell has long held the view that putting out an agenda ahead of midterm elections is a mistake — at least for Senate Republicans, the sources told Axios.

He believes his view has been vindicated by recent history. McConnell points, in particular, to when he led Republicans to win back the Senate in the 2014 midterms without proposing an agenda.

Some donors and operatives point to a different memory: the "Contract with America." House Republicans released a governing action plan before the 1994 midterm elections, and their party won back unified control of Congress for the first time in nearly 50 years.

The current House minority leader, Kevin McCarthy, is a "Contract with America" guy. He's told his colleagues he thinks it's important they tell voters what they support — not just what they oppose.

Both have history on their side. And neither leader is wrong in their strategic approaches, even within the same election year.

It’s happened before.

Senate Republicans did not embrace the House’s “Contract With America” in 1994. There was no such agenda in 2010 or 2014 when House and Senate Republicans enjoyed significant gains and subsequent congressional majorities. In contrast, I can find no such congressional Democratic “agenda” from any of their past elections, including the 2006 and 2008 elections when they recaptured and expanded majorities in the House and Senate towards the end of the George W. Bush presidency. Democrats just ran against Bush.

Yes, Senate Republicans came up with their own agenda in 1994 after they eschewed invitations from House GOP leaders to join them in the Contract With America. Entitled “Seven More in ‘94,” it was a seven-part set of tax, budget, healthcare, and other commitments led by then-National Republican Senatorial Committee chair Phil Gramm (R-TX) and his election team. It’s hard to find, and my copy is in deep storage. It was overshadowed by the House GOP Contract. Ultimately, in retrospect, it didn't matter much. The GOP had a great political environment and terrific candidates like famous heart-lung transplant surgeon (and future Majority Leader) Dr. Bill Frist (R-TN).

But the environment was set and bears much resemblance to this year’s election. First-term President Bill Clinton’s legislative agenda wasn’t proving very popular, including his crime bill (“midnight basketball”), his (and wife Hillary’s) failed work on their complicated universal health care plan, Clinton’s then opposition to welfare reform (he would change), and Social Security tax increases. While the Contract helped Newt lead and control his GOP Conference once they were in charge, whether it helped them win in 1994 remains an open question. Individual components certainly tested well. Clinton smartly co-opted parts of the agenda with his 1996 reelection in focus.

Part of the problem was that Republicans didn’t fully agree on the counter-proposals to some of the Clinton agenda, especially health care reform. Senate Republicans devised two competing bills, one led by U.S. Sen. John Chafee (R-RI) and a more market-oriented proposal by conservative U.S. Sen. Don Nickles (R-OK), co-sponsored by 24 Republicans, a majority of the Conference. I’ll oversimplify by leaps and bounds, but it would have allowed you to shop for health care the way you shop now for auto insurance, with some obvious exceptions. Imagine, health insurance companies actually competing for your business, with insurance plans tailored to your needs? Radical! It remains very attractive but is now largely ignored by the current crop of congressional Republicans. LiMu Emu, call your office.

It’s a problem that plagues Republicans to this day - the inability to coalesce around a single health care reform bill (among other issues). It plagued President Donald Trump’s efforts to “repeal Obamacare.” That is one of several hurdles in developing a unifying plan by committee. And an unfriendly media will focus on both errors of commission and omission.

In 1994, Senate Republicans won 8 seats and captured two more when Democratic Senators Ben Nighthorse Campbell (C.O.) and Richard Shelby (A.L.) switched parties. Meanwhile, House Republicans won 54 seats and its first majority in 40 years. Heady times; a repeat looks likely in November 2022. Maybe including a party switcher.

There are several pros and cons about developing a “Contract With America” type proactive agenda to unify and amplify messages from candidates and incumbents.

Maybe it’s not an “either-or” proposition. Maybe you can do both.

Running on “something” versus “nothing.”

Former U.S. Education Secretary William Bennett once described politics as a football game with no timeouts; either you’re on offense with the ball, driving toward the opponent’s goal line, or your opponent has the ball and driving downfield against you. Having a unifying agenda provides you with an offensive game plan.

This approach makes more sense in a House election environment than in the Senate. All House seats are up every biennial election. House candidates, especially around large media markets, have a more challenging time breaking through with messages on media - they garner less media attention in most cases than do statewide gubernatorial or senatorial elections.

However, in the Senate, only a third of the Senate seats are on the ballot every two years, and the election environments and dynamics are different in each state.

This is complicated because more and more incumbents are less worried about challenges from the other party than their own. A “unifying agenda” may be great for a general election, but for an increasing number of candidates, Democratic and Republican, getting through their primaries is the challenge. This is especially true in House races where gerrymandering has created fewer truly “swing” or competitive districts.

There is also the strategy of “nationalizing” an election. Each major party often turns to that strategy when there is an overriding national issue or environment they think will help them win or turnout voters. Virginia’s Democratic gubernatorial candidate in 2021, former Gov. Terry McAuliffe, tried that approach last year to mobilize Democratic voters. He tried to make the election about Donald Trump. It didn’t work in the face of competing headwinds over education and the economy that drove dramatically higher GOP turnout.

House and Senate leadership roles differ.

Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA) was a controversial firebrand when he finally won his third attempt at a suburban Atlanta congressional district in 1978. A military historian by training, the former college professor wasted little time crafting a vision, strategy, a set of tactics, and operations to do the unthinkable - lead Republicans to a majority in the House.

It took 16 years, but with help, he did it. The GOP would win a Senate majority the same year after an eight-year hiatus. But a majoritarian House, where individual House members have very little influence or power, is very different than leading a Senate Conference. Any Senator can gum up the works under the rules, either by objecting to “unanimous consent” requests - a fundamental management tool - or leading a filibuster. Neither tool exists in the House, where power is obtained through coalitions or caucuses.

While a House speaker may have more influence over committee chairmanships and agendas, a Senate floor leader is “first among equals” and must rely more heavily on persuasive powers than jamming down an agenda. While a House leader can often whip his or her troops into line, a Senate leader’s job is more akin to herding cats, or sometimes, pushing wet noodles up a wall.

Like the institutions themselves, House and Senate leaders operate very differently. As Nancy Pelosi has done, a House Speaker can jam through any bill on a simple majority. Senate leaders don’t have that luxury. It’s why some house members call the U.S. Senate a “graveyard where bills go to die.” True enough. And thank God.

Framing the attack versus offering a target

Senator McConnell understands the long game - the title of his biography - better than most. First elected in an upset Senate election in 1984 with ads crafted by Larry McCarthy and Roger Ailes, McConnell is a legendary political and legislative strategist. McConnell understands the Senate, its rules, and traditions. He knows how to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em and when to walk away or run from the legislative poker table (with apologies to the late Kenny Rogers). He’s occasionally wrong, but rarely.

And McConnell isn’t just thinking about the 2022 elections. He’s thinking about what happens afterward when he recaptures the title “Majority Leader.” He likely doesn’t want to limit options or tie them to an agenda that may not be achievable in a Senate that requires 60 votes to pass any legislative item other than budget and reconciliation bills. After all, there are elections in 2024, when presidential nominees set the agenda. Hold your horses. And 2026 is just around the corner. Forward-thinking.

House GOP leader McCarthy is also thinking about what happens after the 2022 elections. The “Commitment” will help the new Speaker keep his Conference focused and disciplined after they win a majority. The Senate’s ability to serve as a legislative graveyard (excuse me, the “cooling saucer of democracy”) frustrates both parties, but next time it will be Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer playing the role of Grim Reaper in 2023, rediscovering his lost love, the filibuster. Queue up the 2024 talking points. See how this works? History rhymes, indeed.

Senate leaders constantly talk to their colleagues, take temperatures, and figure out their wants and needs. The smart ones never get too far out front of their Conference. They know the length of their leashes. Joe Biden and Democrats have handed McConnell a target-rich environment for victory this fall. Polling clearly shows that much of the Democratic agenda and Biden’s job performance is unpopular with most Americans, including (especially) independents.

McConnell appears to have calculated that given dismal Democratic poll numbers, he doesn’t need to present a pro-active agenda to win a majority. Why offer Democrats a target? A good offense takes many forms, from advocating an agenda to attacking your opponents for theirs. Both are required and especially helpful in debates and campaign advertising. McConnell is happy to let Senate candidates do so of their own accord.

Some of McConnell’s critics may point to Gov. Youngkin’s proactive agenda in Virginia’s gubernatorial election last fall. And it served him well, drawing salient contrasts after eight years of increasing progressive if not sclerotic Democratic governance. But it wasn’t a “national” agenda - it was homegrown, all Virginia.

Youngkin’s win was as much about him and his style as a first-time outsider candidate with an attractive, optimistic, and energetic demeanor as his robust agenda. And Youngkin’s agenda derived much from Democratic mistakes, especially McAuliffe’s debate gaffe that parents shouldn’t be telling schools what they should teach. An agile Youngkin campaign pounced. References to Biden and his shameful Afghanistan surrender were made, but not emphasized.

With different dynamics, can Republicans have it both ways? Does having a pro-active agenda help them in the House, while Senate Republicans hold incumbent Democrats accountable and hoist their sails, relying on prevailing political winds? The answer, for now, appears to be yes. More from the Axios story:

Between the lines: A top GOP operative, who didn't attend the dinner but has often heard such conversations involving McConnell, said these kinds of discussions happen regularly with the Republican leader.

"It happens all the time," the source told Axios. "Donors especially are always asking for an agenda of some kind and McConnell pushes back hard. Because he knows that all it does is take the focus off unpopular Dem policies and gives Dems something tangible to tear apart."

"One of the biggest mistakes challengers often make is thinking campaigns are about them and their ideas," the source continued. "No one gives a (expletive deleted) about that. Elections are referendums on incumbents."

"Challengers need to keep the focus on what incumbents promised and point out how they failed to deliver and how that has negatively impacted voters' lives," the source said.

The bottom line: Current polls appear to support McConnell's political calculation.

By almost any measure — from President Biden's approval rating to the generic ballot — Republicans are enjoying their best political environment for a decade.

They're in this position having barely uttered a word about their plans for the future

Conservatives critical of McConnell’s strategy better channel their energy to help House Republicans develop their plan and abandon circular firing squads around the Senate.

In 2022, House and Senate Republicans may be able to have their ice cream and eat it, too.

(Disclosure: The author was Staff Director for the U.S. Senate Republican Policy Committee, chaired by US Sen. Don Nickles, from 1992-1995. He was the Secretary of the US Senate during the 104th Congress, 1995-96).