Celebrating an Anniversary

Thirty years ago today, I was sworn in as the 28th occupant of a historic position: Secretary of the US Senate. Here's a primer on that position and the subculture that helps the Senate function.

Last week, I was able to take advantage of something I’d not been able to do since 9/11 - a walk up the Capitol dome’s 383 steps to its top, just below Lady Liberty. It brought back a lot of memories of nearly two dozen “dome tours” I’d led between 1995 and late 2001.

I was able to do so courtesy of the Secretary of the Senate, Jacqueline Barber, the 35th occupant of a position, the origins of which date back to the first days of the first Congress in 1790, when the Senate gathered in its “upper chamber” on the second floor of our then-Congress assembled in Philadelphia while Washington, DC’s Capitol was being constructed. Dome tours came to a halt after 9/11 and again during a major Capitol renovation between 2014 and 2016 to repair cracks in the 150-year-old, nine-million-pound cast-iron edifice.

There is no “official count” of the steps to the top of the dome. Twenty-eight years ago, I asked my then-seven-year-old son, who’d been to the top with me a couple of times, to count the steps. He proudly announced “383” as we concluded. Official enough for me.

No visit to Philadelphia’s famous Constitution Hall, where the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution of the United States were drafted, is complete without a short walk next door to Congress Hall. The understated, even plain, first floor housed the House Chamber, where John Adams was sworn in as the nation's second President. A trip upstairs will lead to the much more ornate Senate chamber, which resembles a smaller version of one used between 1810 and 1860, and even bears a resemblance to the current one. After all, there were only 26 Senators - two from each state, and getting a quorum was difficult. It took the Senate three days to assemble a quorum during its first days.

The Senate has occupied four chambers throughout its existence, excluding temporary arrangements made after the British Army burned the Capitol in 1814. With the help of an expert tour guide, scars of that incursion can still be found today in a circular stairwell leading up to Statuary Hall in the form of musket ball marks. I love pointing out the “scars” of history throughout the Capitol.

Washington was first sworn in at Federal Hall in New York City. His second inauguration took place in the Senate Chamber of the Congress Hall. The Senate has always been the “official” host of the presidential inauguration. Washington was unopposed for both his terms, and he famously refused to run for a third.

When the first Congress finally assembled on December 6, 1790, they quickly realized the need for officers and staff to help them conduct business. The first one was a Doorkeeper, responsible for maintaining order in and around the chamber. It was quickly followed by the selection of Vice President Adams’ friend, Samuel Otis, the former Speaker of the Massachusetts legislature, as its first Secretary. Otis kept the Senate’s records, referred bills to their first committees, ensured that Senators collected their $6 per day salaries, and maintained a sizable office just off the Senate’s chamber. Large portraits of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette adorned committee rooms as a gesture of appreciation for their support during the American Revolution. Rebellious French had other thoughts a few years later. They’re still there.

Otis would serve 25 years as Secretary of the Senate, dying in office. Otis remains the Senate’s longest-serving Secretary.

The Secretary of the Senate is the senior officer of the United States Senate, leading an operation comprising 24 offices and over 220 staff. The Secretary serves as the Senate’s chief legislative, administrative, and financial officer. Their signature is the one featured on the paychecks every Senator and staff member receives. The more “famous” Senate official, the Parliamentarian, reports to the Secretary. Other offices include the Public Records office, where campaign and personal financial disclosures are filed and maintained; the Historical Office; the Chief Counsel for Employment, the Curator of Art, the Document Room (where hard copies of bills are preserved and still available to the public), and dozens more, including a gift shop. There’s so much more, including the Official Reporters of Debate, who are responsible for what goes into the Senate pages of the Congressional Record.

It’s the only one of the Senate’s five elected (by them) who are sworn in on the Senate floor.

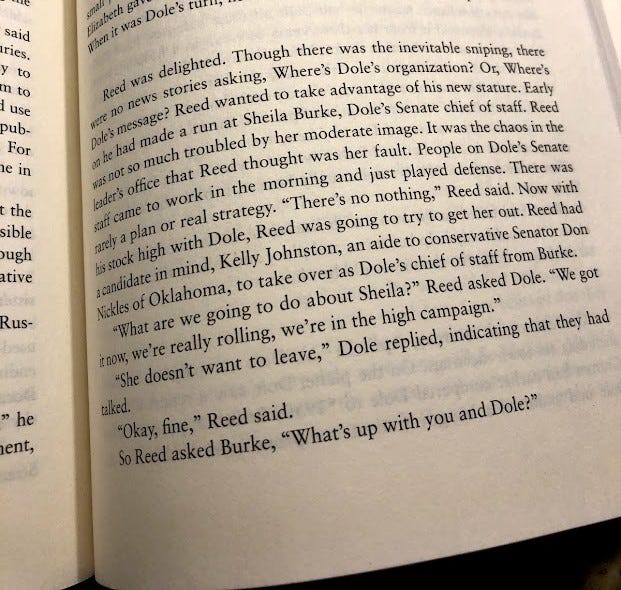

Barber is the Senate’s 35th Secretary. I was number 28, sworn in on this day exactly 30 years ago during the historic 104th Congress. How I obtained the position was written by Bob Woodward in “The Choice,” a book about the 1996 presidential contest between Senator Bob Dole (R-KS) and President Bill Clinton. It was Dole, as the Senate’s new Majority Leader, who nominated me for the position about 5 months after the 104th Congress convened. His Chief of Staff, Sheila Burke, simultaneously held both positions until Dole could settle on a nominee, customarily confirmed by a unanimous voice vote.

Secretary of the Senate is not a job one aspires to. It just “happens” to the right person in the right spot at the right time.

I wasn’t Dole’s first choice—and probably not his second, third, or fourth. Dole was seeking someone with strong outside political connections, preferably a heavyweight lobbyist, as he prepared to run for President after the GOP won control of Congress in 1994, known as the “Contract With America” election. When no one to his liking wanted the job, due to a then-one-year lobbying ban upon leaving office, he looked inside. He found a 38-year-old staff director for the Senate Republican Policy Committee, who led a leadership office for his friend and future candidate for the vice presidential nomination, U.S. Sen. Don Nickles (R-OK). Dole would eventually settle on former US Rep. and Buffalo Bills football legend Jack Kemp as his running mate. Conservative Senators and outside groups trusted me, and that was enough for Dole, who was looking to cement his right flank for the upcoming election.

Dole campaign manager, Scott Reed, preferred me as Chief of Staff to Dole, where, as a long-time congressional campaign operative, I could help coordinate the workings of Dole’s leadership office with the presidential campaign. However, Dole was reluctant to depart with his long-time and loyal chief of staff, Burke, whom Reed wanted to move into the Secretary’s office. Instead, the roles were reversed. I suspect Dole was also reluctant to politicize the operation of the Senate, although Democrats had no qualms about doing so to him.

The rest, of course, is history. Dole, finding it challenging to be pinned down with Senate business while running for President, opted in the summer of 1996 to resign altogether from the Senate. I would remain on as Secretary for Trent Lott (R-MS), who had served as the Assistant GOP Leader and replaced Dole. Nickles would replace Lott. But while Lott asked me to stay through that Congress, I knew he would eventually want to replace me with his person. Thus is the nature of the job.

Woodward, in his book, derisively referred to the position as a “factotum.” That’s wildly unfair and ignorant, but I understand why he came to that conclusion.

I remained around long enough to conduct the orientation for 16 newly elected U.S. senators that year, a large class of mainly former House Members, and scooted off to begin a 21-year career as a food industry lobbyist. But not until after an interesting experience as a nominee for the Federal Election Commission. I pulled my own nomination, made by President Clinton upon Dole’s recommendation, after Senate Democrats wanted to trade my nomination and one other for seven Democratic federal judges. And proudly so, despite going through two full-field background investigations. The Clinton folks did not want me on the FEC, but couldn’t find any dirt. I took seven judges down with me—a fair trade, in my estimation.

This is the Clinton’s were talking about. Monica Lewinsky, call your office.

My tenure as Secretary was relatively short, lasting less than two years, but it was eventful and personally impactful. It changed my life and turned me into a lifetime ambassador for the US Senate, its history, and how it works (and sometimes doesn’t). I like to think that I helped make the Senate a better place.

Not to brag, but I’m probably the most media-savvy Secretary in history, with dozens of appearances on C-SPAN and other outlets, both during and after my time as Secretary. I had good relationships with the Capitol press corps, but didn’t engage in the “anonymous sourcing” that seems to dominate these days. With rare exception, if I couldn’t be on the record, I wasn’t interested in being a part of the story. When U.S. Sen. Phil Gramm (R-TX), amid a challenging reelection in 1996, asked me to step in with Texas reporters over a false accusation that he had overspent his official office account, I was happy to do so. He was grateful and was handily reelected.

Most Secretaries and Senate officers eschew the limelight, and probably for good reason. We know stuff and live in fear of saying too much or the wrong thing, or offending someone. Senators don’t like officers or staff stealing the limelight, but I never did that. Much of my media orientation came from my background as a journalist and press secretary on Capitol Hill, as well as in a few high-profile campaigns. Beginning before I became Secretary, I’d also served as the host for several call-in television shows for U.S. Senators, broadcast back to their states via the Senate’s Recording Studio to cable TV outlets. They included Senators Trent Lott, Al D’Amato (R-NY), John Ashcroft (R-MO), Nickles, and my personal favorite, the current President Pro Tempore, Chuck Grassley (R-IA), whose show I moderated for nearly 15 years until he canceled it due to rising costs. I performed that role for more than a decade, and loved every show. I was never paid for doing them.

A former college Thespian, I was comfortable on stage and in front of cameras and microphones. I found that it served me well on occasion; other times, not so much. I heard a few grumbles from other Senate leadership staff, but no Senator ever complained, at least to me. Before I became the Senate’s Secretary, with the help of Will Feltus and the staff at the Senate Republican Conference, we launched a Monday morning television show on the Senate GOP’s internal TV channel, covering the week ahead legislatively, complete with interviews with Senators. I loved reprising my journalism background. My female host and I were derisively called the “Regis (Philbin) and Kathy (Gifford) Show,” named after a popular morning show at the time, but I took it in stride.

The job does come with certain lifetime privileges, mostly access to the Capitol building, the Senate’s Library, and the cache that comes with being a member of the Senate’s “extended family.” As a “has-been,” I had a little more freedom to discuss controversial Senate issues, such as the use of laptops on the Senate floor (still a no-no), after I left in 1997. Now that I’m no longer a lobbyist, I also have access to the Senate floor while it’s in session, but I very rarely take advantage of it. I just don’t belong there. I’m invited by friends, such as national morning radio host Chris Stigall and a few podcasters, to explain the Senate and its politics on their programs to their audiences.

I still enjoy leading the occasional tours of the Capitol for organizations I’ve worked with, including the Embassy of Canada, who seem to know more about our history than many of our citizens. They make marvelous guests.

I have many stories from my tenure that I would love to share here, but space and discretion won’t allow. I’ve shared many of them in previous posts over the past couple of years. They include participating in interparliamentary meetings with legislators from around the world and joining a US-Canadian delegation of legislators in British Columbia, Alaska, and Yukon in 1996. I’ve also represented the US Senate at a meeting of the Inter-Parliamentary Union in Istanbul in 1996, when, with the help of the Canadian delegation that I befriended, I successfully encouraged them to adjust their schedules so that US Senators could participate (The IPU is the global fraternity of legislators). The US, led by then-Speaker Newt Gingrich, later terminated Congress’s participation, which I consider a mistake and a lost opportunity, given the surge of democracy that followed the 1989 fall of the Soviet Union.

The 104th Congress achieved a significant amount of reform, including the enactment of the Congressional Accountability Act, its first law, which required Congress to apply to itself many of the same rules that applied to the private sector, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act. I took the leadership role in helping Senate offices comply with the new law, which was not without controversy. Congress also enacted its first major lobbying disclosure reform law, with the House Clerk (my counterpart) and I writing the first implementing regulations. I also went on the road with 22 briefings for the lobbying community on the new act, soliciting input and answering questions. My role was to ensure compliance, and I took it seriously.

The late Senator John Warner (R-VA), then Chairman of the Senate Rules Committee, and I announced the launch of the Senate’s website in 1995. Chairman Warner and his Committee oversaw my operations, a role he took seriously. I loved working with the legendary US Senator, who invited me to special events at his historic home, Atoka, a former Civil War hospital, not far from where I now live. The Senate’s website, initially orchestrated by Cheri Allen, whom I brought to the Secretary’s office from my former position, remains an outstanding resource and is superbly accessible.

And while the position was largely nonpolitical and nonpartisan, I still helped facilitate the care of U.S. senators participating in Dole’s 1996 RNC nominating convention in San Diego, establishing and operating the first-ever “Senators Cloakroom.” Democrats had been doing that for years previously, and I was catching up. GOP Senators loved it, and Senator Dole and his campaign appreciated the ability to keep tabs on and in contact with Senate surrogates.

What I’m most proud of is this: A day after being sworn in, freshman US Sen. Rick Santorum (R-PA), a newly elected Senator bent on reforming the institution, directed me to reduce my spending by 15 percent (Senate appropriators later reduced that to a 12.5 percent cut). I reduced my overhead from 230 positions to 214, all through attrition. I reorganized and professionalized operations while assuming new responsibilities to implement the Congressional Accountability and Lobbying Reform Act. And I followed up with a proposal to freeze spending the following year.

Don’t tell me federal spending can’t be cut. Of course it can.

The Secretary’s position comes with a responsibility to educate the public on the history and significance of the US Senate, a responsibility I continue to embrace as a former official. My exposure to, and interest in, the Senate’s history has had a profound impact on me, and I have taken the opportunity to share it when and where possible.

And it’s never been more critical. We live in contentious times, and our educational institutions have done a pathetic job of teaching how Congress works. Faith in our institutions, including Congress, is in decline. Very few in the media - Chad Pergram of Fox News is a rare exception - do a respectable job of examining and explaining the machinations that often appear opaque or confusing to so many Americans. I’ve tried to blast through that as one of the primary missions of this modest blog site, and will continue to do so. Despite all the conflict you read and hear about, the place still functions pretty much the way our framers designed it.

Rising to professional heights - even to the top of the Capitol dome - gives one a unique perspective that is often lost amidst the forest and the weeds. It can, and should be, humbling. “If you ever get tired of seeing that,” a former boss of mine told me as we drove towards the Capitol after a lunch in 1979, “leave.” I never tire of admiring the world’s great symbol of democracy, and I love every visit.

So, thank you for allowing me to share this memorable holiday and milestone in my life with you. I am forever indebted to the three U.S. senators who made this special journey possible, especially the late Robert J. Dole, along with Don Nickles and Trent Lott, as well as to all the friends and colleagues on Capitol Hill during this time who continue to inspire me today. You know who you are.

I was a newbie, a House LA in 1995. I wouldn't get over to the Senate until 2001. The Senate of the 90s were giants, substantively and politically.

Great story, Kelly, and a salute to your knowledge and skills. I can't believe I even knew you before you received that assignment/honor.