A Constitutional Right to . . . Food?

Maine Voters Amended Their Constitution Tuesday to Include a “Right to Food.” What Does That Even Mean? We Might Ask the Raw Milk Promoters

One of the more interesting ballot questions last Tuesday was Question 3 in Maine. The 43-word constitutional amendment, overwhelmingly approved by voters, reads as follows:

“All individuals have a natural, inherent and unalienable right to food, including the right to save and exchange seeds and the right to grow, raise, harvest, produce and consume food of their own choosing for their own nourishment, sustenance, bodily health and well-being, as long as an individual does not commit trespassing, theft, poaching or other abuses of private property rights, public lants, or natural resources in the harvesting, production or acquisition of food.”

It’s a little hard to figure out precisely what this means.

The coalitions supporting and opposing the initiative were bipartisan and unusual. Democratic legislators joined Republicans in support. Animal rights organizations joined the Maine Farm Bureau and Maine Potato Growers Council in opposition.

But no one seemed to care enough to invest much money in the campaign. A total of less than $8,000 was spent by both sides to influence the outcome.

Ballotpedia’s quote of Republican St. Rep. Billy Bob Falkingham, the author of the amendment, best explains its scope and purpose:

"Jumping ahead 25 or 50 years into the future, could we see our government creating roadblocks and restrictions to the people’s right to food? Will the government be telling people what they are allowed to eat and where they can grow it? Will Monsanto own all the seeds, and will we have gotten so far from our roots that we won’t even have natural seeds anymore? Will people even be allowed to grow gardens? Or will gardening become a luxury reserved for the rich? ... Will we need it, 25, 33, or 50 years from now? If we wait until then to find out, it will be too late."

Does that include federal patent and trademark laws since seed companies spend millions to engineer their seeds through hybridization or genetic manipulation to help farms produce more crops?

Faulkingham, a lobster fisherman by trade, is somehow worried that the government and corporations will prevent people from growing gardens, saving, and exchanging seeds. “There’s a lot of disturbing trends in the food category, with the power and control that corporations are taking over our food,” Faulkingham told Associated Press. That’s about as specific as the “right to food” gets. Good luck, judges and justices. I know of no food company plan to rid the nation of community or personal gardens.

Animal rights activists were opposed, fearful that Question 3 would open doors to animal cruelty.

Oh, sure, there is a long history of the “right to hunt and fish” and provisions in various state laws. Twenty-three states have such laws. A 24th, California (of course) grants a right to fish but not to hunt. Vermont was the first to constitutionalize it in 1777. Other states have or have contemplated “right to farm” provisions. But this is different, and courts will have to decide what it means and how far it goes.

And for food regulators and food makers, what other states will follow suit? And speaking of suits, how will the first lawsuits by farmers or others, using the law, look like, and against whom? I’m sure some enterprising food trial lawyers already have their thinking caps on, involving a sympathetic farmer and a food retailer with big pockets and lots of pricing power in the market, such as Walmart. So do others.

And that’s ultimately what this may be about. Follow the money.

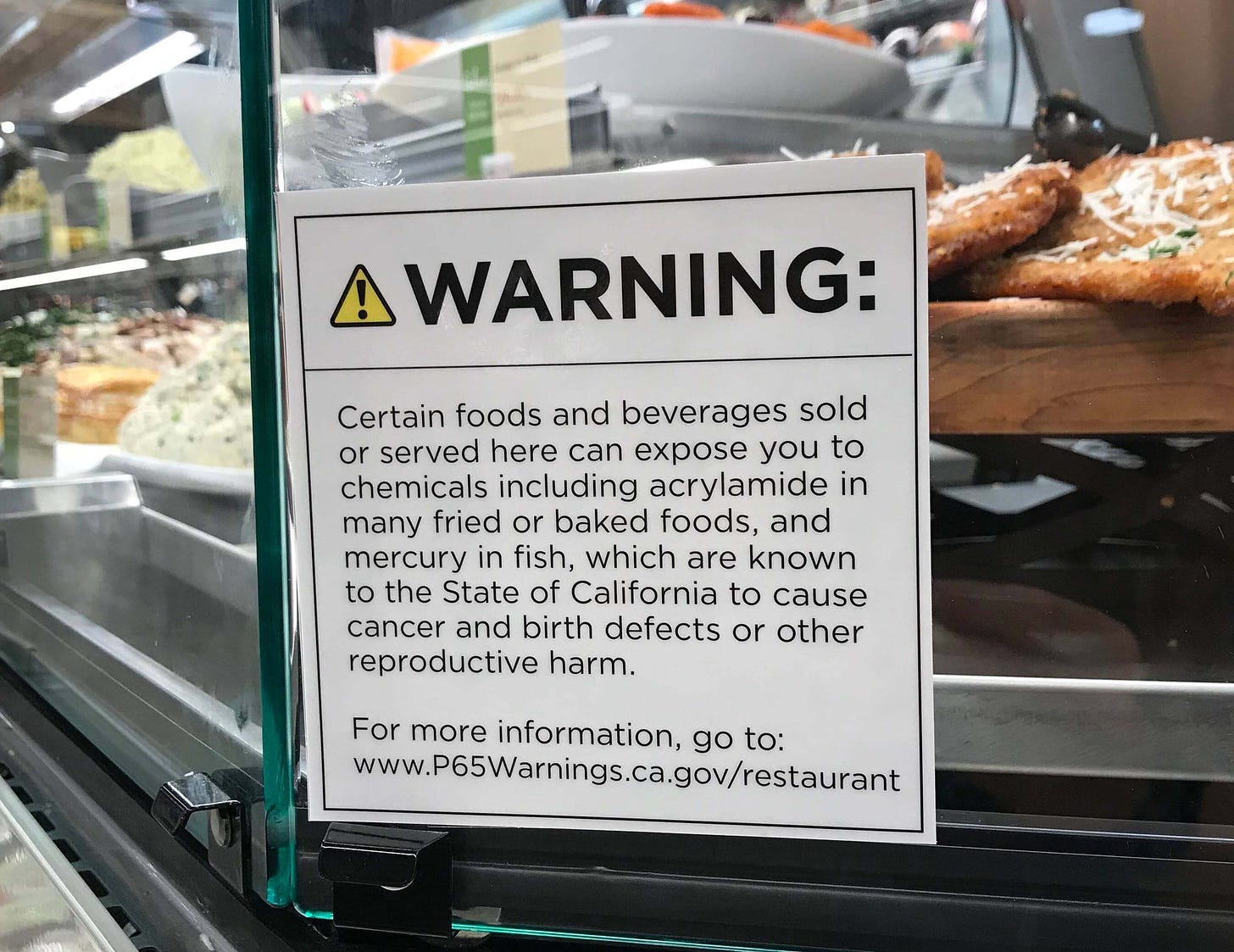

While Maine has a long history of quirkiness on food issues, California is right there with them, from “anti-confinement” laws for pigs and chickens to requiring warning labels on foods that contain chemicals known to cause cancer or congenital disabilities, like alcohol. Proposition 65 warning labels are so ubiquitous in California that most people ignore them.

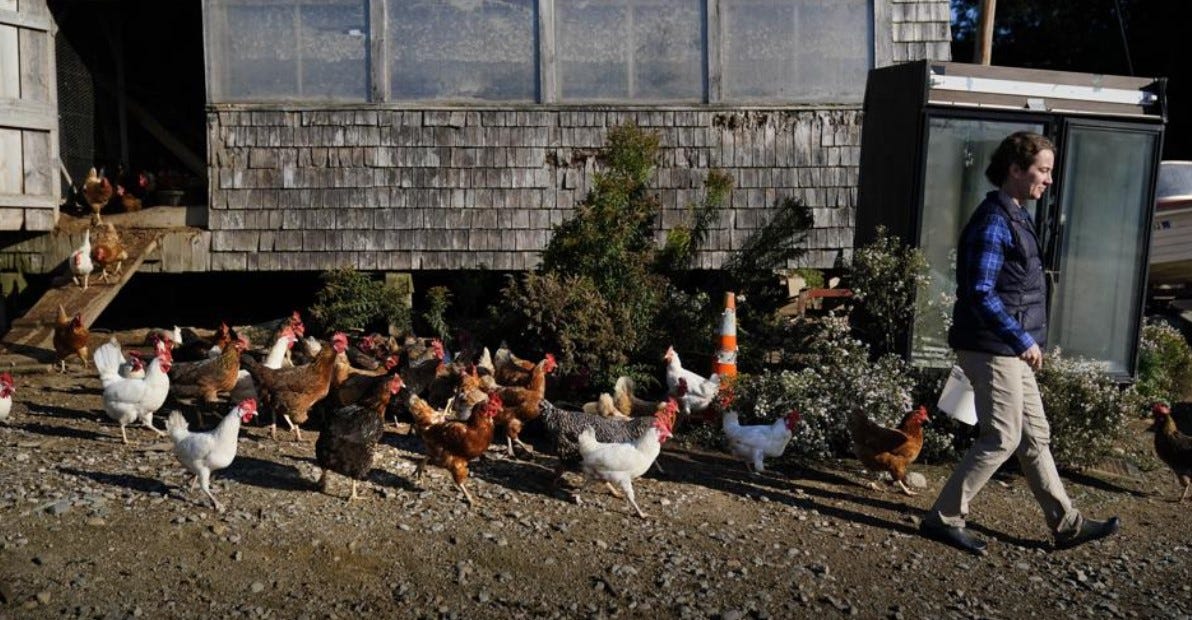

All this has emerged under various rubrics, such as “food sovereignty” or simply “the food movement.” Like all movements and revolutions, it has its patron saints and celebrities. It is motivated by farm-to-consumer relationships and access to “pure,” “fresh,” or “natural” food untainted by corporate middlemen, bigness, technology, and things like preservatives, flavorings, artificial fertilizers, colors, and other attributes found in many packaged foods. It reflects an emotional and romantic, if not religious, desire to connect more closely to food. They believe they taste better and are healthier for you, a matter of long-standing debate. These are the folks behind the explosion of farmers’ markets in urban/suburban settings over the past several years.

Food involves all our senses and connects us to special events in our lives. What significant life moments, at least the celebratory ones, don’t include food? Food issues are also sadly and tragically used as a weapon to scare people and raise money.

Convenience and price are often overlooked or ignored. And tragically, so is food safety.

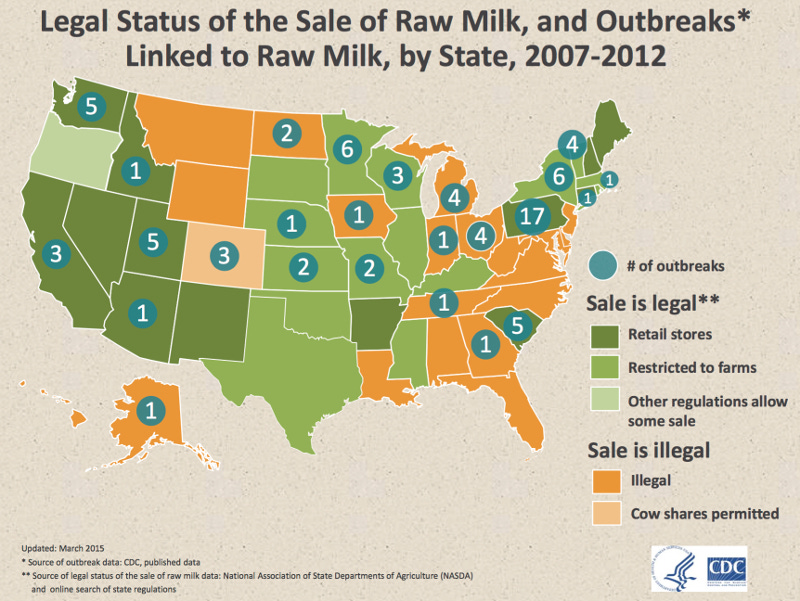

There is no better example of that than the long-standing debate over raw milk consumption. While the US Food and Drug Administration outlaws the interstate sales of raw milk and the Centers for Disease Control warn against human consumption, it is legal in most states. Just 13 states outright prohibit retail or farm sales, although a couple allows you to access raw milk through “cow sharing” arrangements with farmers and fellow consumers.

And yes, raw milk consumption is dangerous. Let’s consult the Centers for Disease Control via foodsafetynews.com:

Based on statistics from the five-year period 2009-2014, people who drink unpasteurized, raw milk are 840 times more likely to contract a foodborne illness than those who drink pasteurized milk.

The statistics, included in a research report scheduled for publication in the upcoming June issue of “Emerging Infectious Diseases” also show raw milk drinkers are 45 times more likely to be hospitalized if they get sick than people who become ill from drinking pasteurized milk.

“Unpasteurized milk, consumed by only 3.2 percent of the (U.S.) population, and cheese, consumed by only 1.6 percent of the population, caused 96 percent of illnesses caused by contaminated dairy products,” according to the report scheduled for June publication by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

And the raw milk industry might be the biggest winner in the “right to food” campaign.

Just in case you’re in doubt about the danger of raw milk, let’s consult members of the West Virginia legislature just after they celebrated the legalization of retail raw milk sales in 2016 in the state by drinking it. Maybe they should have stuck with champaign.

I get the philosophical argument, and I’m entirely aware of the emotion it engenders. I’ve been on the receiving end. It’s the same with motorcycle riders about wearing helmets, and many others: “my body, my choice.” Except your decision to consume raw milk might send you to a hospital, and if you don’t have insurance, and even if you do, the rest of us will be paying the bill through higher insurance rates or tax dollars through Medicare or Medicaid. Medical professionals, who are kind of busy right now, will be diverted. Sometimes, we have a responsibility to own the full consequences of our optional decisions. Please don’t make the rest of us pay for your stupidity.

Do you want to embrace libertarianism? Then go The Full Monty: your body, your choice, your expense.

This is one issue where Republicans can be just as stupid as Democrats. And if you think feeding raw milk to your children will help them, think again. You might as just as well introduce them to Russian Roulette. If you’re not familiar with that, this clip from the Academy Award-winning “Deer Hunter” from 1978 will show you how it works. I wouldn’t show this to young children. Or serve them raw milk.

While the CDC and FDA may have - well, did - screw up the messaging of COVID vaccines, they at least got this issue right.

No one person has done more for food safety than the legendary Dr. Louis Pasteur, who discovered that treating foods with heat for short periods destroyed bacteria and other pathogens that made people sick.

Take the canned food in your store. There is nothing safer, and few things more affordable. Corn, spinach, peas, and more are picked at the peak of freshness and, usually within four hours, are sorted, washed, fed into a can, sealed, and placed into a “retort” or spiral cooker that heats the products in the sealed can for a specified period. The process of canning preserves foods without chemicals. Cooking the product in the can kills harmful bacteria without destroying other beneficial characteristics. Yes, vitamin C, which is heat-sensitive, is lost in the “pasteurization” process. But most other things like fiber and other vitamins remain. And canning keeps it safe for a couple of years before the quality slowly starts to be lost. Frozen food has similar advantages over a shorter period. No such luck with fresh products, which have their place as well.

But canned foods are not “fashionable” for reasons that escape me. Canned foods are affordable and perhaps the most valuable entities of our food supply. Steel and aluminum cans are recyclable. Condensed soup, invented more than a century ago, was America’s first truly “sustainable” food. But they don’t appear “fresh” or “local” to “foodies.” The food world has lots of work to do on educating Americans on the safety and efficacy of our food supply. It is truly miraculous, even with today’s government-induced supply chain challenges.

Maine’s “Right to Food” amendment may start a trend, supported by raw milk apostles and others with unsubstantiated and false notions of food that move to other states. It’s a vague if not terrible law with potentially severe consequences. Don’t let it take root in your state, and let’s hope judges strike this down as vague and wholly unenforceable law and make it go away.