A Capitol Tour, Part II

We start in the Senate's "Reception Room." Part of a series touring your US Capitol.

As Capitol architects began designing the new House and Senate chambers during the mid-19th century, they needed to address the reality that the country was expanding rapidly. President Knox’s “Manifest Destiny” and treasures, perceived or otherwise, on western lands created the environment to admit new states.

That meant more Members of Congress in the House and the Senate. And with it, more constituents visit the Capitol to petition their elected officials (see: First Amendment). They needed a place to greet them.

Thus, the Senate’s Reception Room is located at the Capitol’s northeast corner adjacent to the vice president’s Senate offices and the chamber (reminder: the Vice President is the President of the Senate). It’s one of the few rooms on the Senate’s wing resulting from the 1860 expansion that still serves its original purpose. The Senate’s post office, originally designed to be the library, which received critical messages during the Civil War, is now the LBJ Room. It was his office as Majority and vice president before the Kennedy assassination. Democrats hold their weekly Tuesday caucus luncheons here. It’s under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Senate.

Constantino Brumidi, the Italian Renaissance painter who gave his career - his life - to the Capitol, particularly the Apotheosis of George Washington and the Brumidi Corridor, painted parts but not all of the reception room. He wanted to leave plenty of room for a country whose story was still being told.

At eye level, the ornate room features five portraits of the most important Senators ever elected, as chosen by a special Senate committee chaired by then-freshman John F. Kennedy (D-MA). In the center of the room, along its south wall facing north, is Henry Clay (Whig-KY), remembered in history books as “The Great Compromiser.” Clay, elected Speaker of the House as a freshman, ran unsuccessfully for president three times and was the architect of several pre-Civil War era bills that delayed but did not prevent the outbreak of hostilities.

Positioned to Clay’s right, and seen in the photo above, is John Calhoun, a South Carolina native and “States Rights,” slaveowner, and “nullification” advocate who also served as Vice President under two presidents (John Q. Adams and Jackson), Secretary of War (Monroe) and Secretary of State (Tyler and Polk).

Your eyes are inevitably drawn toward an equally ornate floor with stunning encaustic tiles forged at a Minton tile factory in Stratford-Upon-Trent, Staffordshire, England. While the tiles have proven durable, they are not indestructible. Fortunately, a factory still exists at Stratford-Upon-Trent to provide replacements.

Opposite Calhoun is the legendary abolitionist Daniel Webster (Whig-New Hampshire). Webster also founded the Senate’s Page program, which lives on, unlike the House Page program.

A brief word about the Senate Page program, which I love. Pages were moved to a well-supervised Webster Hall, a former mortuary, shortly before I became Secretary in 1995. I was also responsible for the education of the Pages. They are selected to serve during their junior year of high school. Others are selected for 3-4 week periods during the summer until the traditional August recess (either entering or having completed their junior year). When the Senate was in session, classes began around 6 a.m. and ended before reporting for duty - preceded by a short van trip to the Capitol - around 9 a.m. Classes and field trips are held on weekends. I remember arriving very early one morning to teach a class. I did that once. I’ve never met a page, including my two sons, who were not dramatically affected by their service. Profoundly impactful to young, impressional minds. If only every high school junior could serve as a Page in Washington or any state legislature.

The other two Senators were a little harder to select. And both were Republicans: “Mr. Republican,” GOP Leader Robert Taft Jr. (R-OH) and “Fighting Bob” LaFollette (R-WI). After World War II, Taft crafted the Legislative Reorganization Act that reorganized the Senate, officially establishing leadership positions and separating campaign politics from the chamber. It’s been amended a few times, and each major party’s caucus differs in how they select leaders, but Taft’s handiwork lives on.

The Senate’s biography of LaFollette lists this as the basis for his selection as one of the “famous five.”

Independent and impassioned, La Follette championed such progressive reform measures as regulation of railroads, direct election of senators, and worker protection, while opposing American entry into World War I and condemning wartime restrictions on free speech. He initiated the investigation into the Teapot Dome scandal of the early 1920s and ran for president on the Progressive Party ticket in 1924. In choosing La Follette as one of the "Famous Five" in 1957, the Kennedy committee described him as a "ceaseless battler for the underprivileged" and a "courageous independent" who never wavered from his progressive reform goals.

My favorite story about LaFollette involves a spittoon. He was held back from throwing one at the Senate’s presiding officer for refusing to recognize him.

Since the late 1990s, several additional portraits have been added. They include Robert Wagner (D-NY), author of the National Labor Relations Act and Social Security Act; Arthur Vandenberg (R-MI), a former abolitionist who, in his 1945 “Speech Heard ‘round The World,” announced his conversion to internationalism. “In so doing, he became the embodiment of a bipartisan American approach to the cold war,” according to the Senate’s website.

The originators of “The Great Compromise,” Connecticut’s delegates to the Constitutional Convention and its first two US senators, Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth, are also now featured. They resolved a heated dispute between larger and smaller states over the composition of our two-house Congress. Other than the fact that Senators are now directly elected, their compromise still holds today.

Another room that serves its original purpose is found on the opposite corner - the President’s Room. During the 1860 expansion, a session of Congress and a presidential term would end on the same day every four years (usually March 3rd). The rush to pass and get signed a flurry of last-minute bills resulted in scores of horsedrawn carriages racing down muddy Washington streets, often in the cold winter rain, toward the White House. Architects decided to make it easier on Congress by giving the President access to an office in the Capitol’s northwest corner, just off the second-floor Senate chamber. It’s the corner of the Capitol closest to the White House.

But that changed in 1933 when the 20th Amendment of the Constitution was ratified, which provided that presidential and vice presidential terms would end at 12 noon on January 20th following elections.

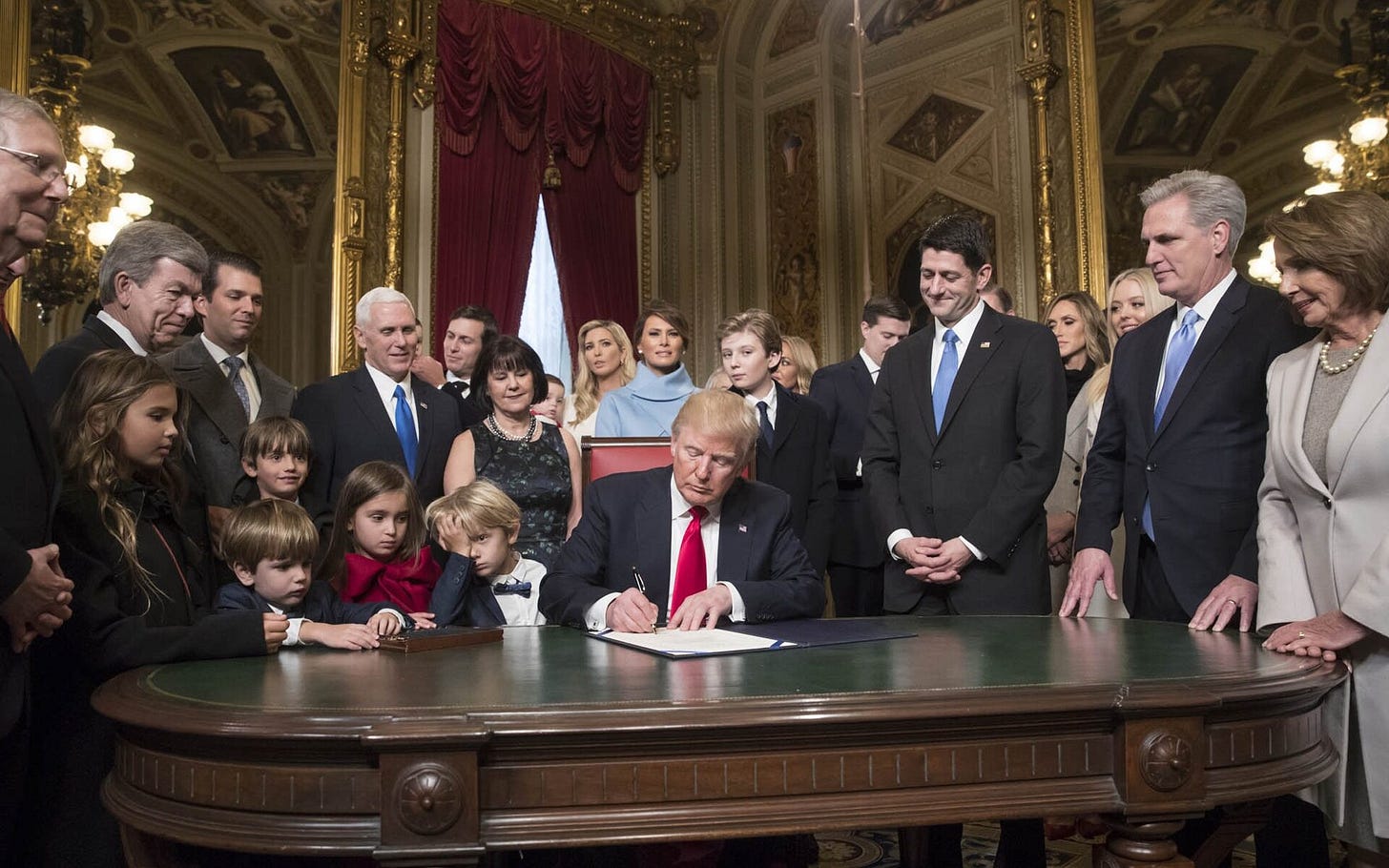

President James Buchanan first used the office just before he left office. He was succeeded by Abraham Lincoln, who made great use of it. He received word (via telegram) in that office of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s offer to end Civil War hostilities in April 1865. Almost every president has used it since, usually on inauguration day, to sign nomination papers for the new cabinet and executive orders.

President Lyndon Johnson used the room to sign the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The room is arguably Brumidi’s finest work other than the Brumidi Corridors, with the room painted Fresco style (oil on wet plaster). It features portraits of President George Washington’s first cabinet. President Washington is featured prominently, surrounded by Thomas Jefferson (Secretary of State), Henry Knox (Secretary of War), Edmund Randolph (Attorney General), and Samuel Osgood (Postmaster General). According to the Architect of the Capitol, “In the corners of the ceiling are four figures representing fundamental aspects of the nation's development: Amerigo Vespucci for Exploration, Christopher Columbus for Discovery, Benjamin Franklin for History, and Pilgrim leader William Brewster for Religion.”

The President’s room is not open to the public. And the fireplace doesn’t work.

One common misperception is that President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in this room, at the desk still found there. Untrue. He signed the proclamation at the White House.

The bronze chandelier is a favorite and one of the few to have survived an 1898 gas explosion at the Capitol. Constructed around 1865, it was electrified and remains with gas tappets still in place. It is one of many impressive chandeliers worth stopping to see when you visit the Capitol.

I’m surprised that C-SPAN still features my 1996 video tour of the President’s Room in its archives and other videos I narrated. Did none of my successors update this? Was it that good? You can watch it here and decide for yourself. No Oscars were nominated or awarded.

I’ll close here with a brief description of the vice president’s office between the Senate floor and the reception room. I’ve only been in it once when Dan Quayle was Vice President. His chief US Senate aide, Bill Gribben, invited me to see Richard Nixon’s oval office desk, which I’m told is there, complete with two holes that housed the infamous bugging devices exposed during the Watergate scandal. Other than the desk and the office’s location, it is unspectacular.

John F. Kennedy also firmly signed a document on the desk, imprinted on the varnish. That is cool.

Next post, we tour the Senate’s current and former chambers. I have more stories.